The Waorani, featured above, are one of the peoples who inhabit the Yasuní forests in Ecuador, along with the Kichwa people as well as two uncontacted groups, the Taegari and Taromenane. IMAGE CREDIT: Amazon Frontlines

- In Ecuador’s snap election, approximately 60% of the electorate voted “yes” to protect the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve from oil exploitation.

- Despite the public rejection of the results of the vote by Ecuador’s Minister of Energy and Mines, the government subsequently issued an official statement reaffirming its commitment to respect the will of the people.

- Efforts to protect the Amazon rainforest must take into account the economic needs of the Indigenous peoples who live there.

On August 20, the people of Ecuador made history by voting to protect Yasuní National Park from further oil drilling. Less than two weeks after the assassination of presidential candidate Fernando Villavicencio, Ecuador demonstrated the power of direct democracy. Despite the increased risk of political violence, 75% of the electorate turned out to make their voices heard. About six in 10 voters said yes to the Yasuní referendum and voted to leave nearly 726 million barrels of crude oil in the ground.

In an unofficial statement three days after the election, the Minister of Energy and Mines Fernando Santos Alvite declared that the government of Guillermo Lasso would ignore the popular vote and grant permission for oil drilling in the region. Less than 24 hours later, the Ecuadorian government reversed course and issued a statement reaffirming its commitment to respect the democratic decision to protect the Yasuní.

The turmoil caused by Minister Santos’s premature and very public decision to reject the results of the referendum illustrates the real and enduring threat to democracy in the region posed by corruption, violence, and oil exploitation, and it underscores the need for vigilance and holding leaders accountable.

Protecting Biodiversity in the Yasuní and Beyond

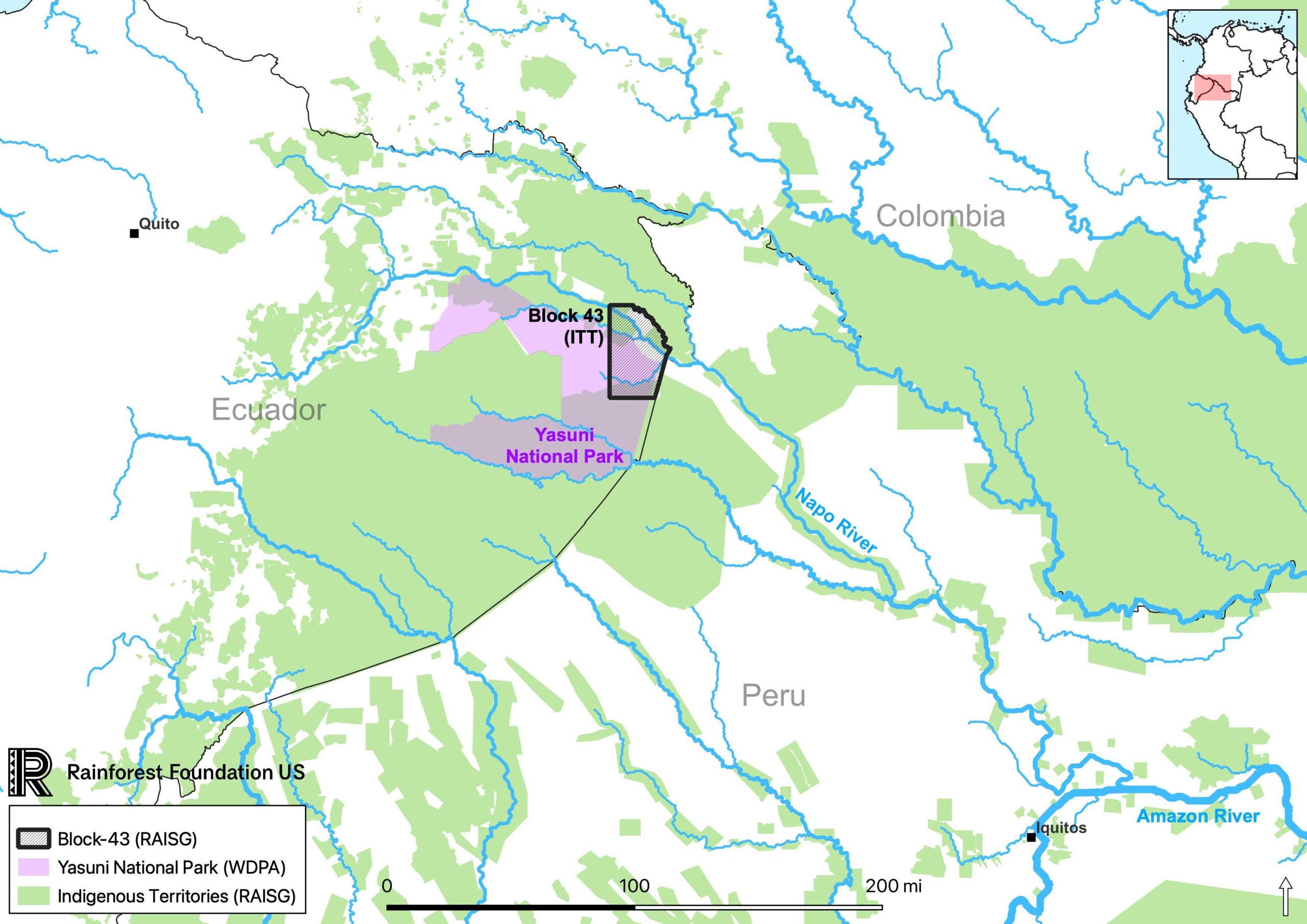

The Yasuní Biosphere Reserve is a 4000-square-mile national park in northeastern Ecuador, on the border with Peru. This unique ecosystem sits at the intersection of three regions: the Andes, the Equator, and the Amazon. Its waterways are part of an interconnected system that feeds into the Napo river, one of the two main tributaries of the Amazon River. As such, an oil spill in the Yasuní would have catastrophic consequences not only for those who live there, but also for downstream communities in Peru.

There may be more species of life in this region than in any other place on Earth. A 2021 study by the Wildlife Conservation Society showed that Yasuní is home to thousands of species, including 1,300 types of trees, 610 bird species, more than 268 kinds of fish, and at least 200 species of mammals, including 13 types of primates.

However, underneath the natural beauty lies Block 43-ITT, Ecuador’s largest oil deposit. Ecuador’s economy has been dependent on oil since exports began in 1972, leading to a decades-long boom in economic growth—and ample opportunities for government corruption.

The Activism of Indigenous Leaders in Ecuador

In addition to being one of the most biodiverse regions in the world, Yasuní National Park is home to the Waorani and Kichwa Indigenous peoples, as well as the 200 to 300 members of the Taegari and Taromenane peoples—the last Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation in Ecuador and those most likely to be negatively impacted by potential oil spills.

“I will defend this until the end because Yasuní is our home. In our own home, we should be consulted first.”- Norma Nenquimo, Vice President of the Waorani Nation of Ecuador.

Because of the activism of Indigenous peoples, Ecuador is a global leader in environmentalism; its 2008 constitution was the world’s first to recognize legally enforceable Rights of Nature, enshrining the Indigenous Kichwa concept of “sumak kawsay,” or a plentiful life in balance with nature. The Indigenous movement in Ecuador has played an important role in defending their territories and the natural world since the beginning.

The Long Road to Direct Democracy

Victory in the fight to protect Yasuní has been the result of dedication and perseverance. Ecuador’s constitution allows for citizens to call a referendum if they can obtain the signatures of 5% of registered voters. In 2014, an organization of environmental activists and Indigenous leaders called Yasunidos (Yasuní United) filed a petition for a referendum to protect Yasuní. The government was incentivized to ignore it, and arbitrarily rejected hundreds of thousands of valid signatures in favor of concessions to oil companies and government corruption.

“The Ecuadorian people decided this ‘yes’ vote, not just the minister. That is the way it should be, with the consultation of the people and the Indigenous nations of Ecuador,” said Nenquimo.

It took almost a decade for Yasunidos to force the government to accept their case and launch the referendum. When the latest referendum was finally approved for the snap election in 2023, it was up to Yasunidos and Ecuador’s Indigenous peoples to launch the campaign to convince the voters to support their cause. The Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) took the lead role in promoting the effort. The referendum provided an opening and an opportunity to fight for the rights of Indigenous peoples to protect their territory.

More Work to be Done

Oil drilling is just one threat to the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve. Narcotrafficking, illegal mining, deforestation, cattle ranching, and porous borders also threaten Ecuador’s democracy and its Indigenous peoples. Political and gang violence is on the rise, and the government seems unwilling to tackle corruption.

To take on any of these problems, local governments and international organizations must provide viable and sustainable economic alternatives. There are internal disagreements among Ecuador’s Indigenous peoples about the role of extractivism in their territory. In fact, 16 Indigenous communities in Orellana province—one of the two provinces where the national park is located—voted against the Yasuní referendum, citing the need for economic advancement and local development. Protecting these territories must be incentivized, and the economic and basic needs of Indigenous peoples must be recognized and incentivized so that resource exploitation stops looking like an attractive opportunity.

When ordinary people have the strength and the courage to make their voices heard, they can enact real change on seemingly intractable issues. Through direct democracy, the people of Ecuador have been able to take on the power of big oil, and secure an astonishing victory for the future of the Amazon.