This article is the third of a series of blog posts produced with Global Forest Watch. The series covers a training initiative for more than 36 indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon to use Rainforest Foundation’s tech-based monitoring strategies and Global Forest Watch’s satellite technologies for combating deforestation. Read the previous post here.

For the community monitors of Buen Jardin de Callaru, a remote community deep in the Peruvian Amazon, the day began early. They had been coordinating with Peruvian enforcement authorities for weeks. The objective: to arrest the culprits of illegal deforestation. To make such an arrest in Peru, authorities have to catch the culprits in the act, which is why it was crucial the group set out as soon as the sun rose.

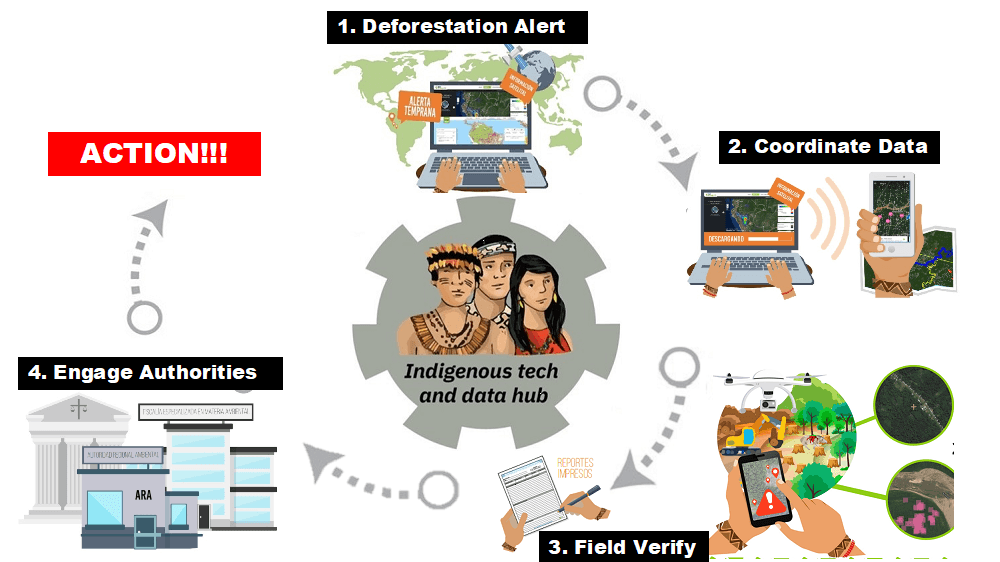

Pablo Garcia, Miguel Riviera and Maria Montoya were selected by their village to be on the frontlines of forest defense. Using smartphones programmed with maps showing recent GLAD deforestation alerts from Global Forest Watch (GFW), they conduct frequent patrols of their ancestral and titled territory to document evidence of illegal deforestation. In September of 2018, they discovered a large clearing. Investigating a recent GLAD alert in the southwest corner of the community territory, the monitors found almost seven hectares of recently burned forest. In place of the trees they found nascent coca plants, illegal in this area of Peru.

At the crossroads of deforestation

Buen Jardín de Callaru is an indigenous Ticuna community in the Bajo Amazonas, a region in northern Peru. The community settled on the Callaru River in the 19th century after rubber industry interests pushed them off their original territory. The village has no formal source of income and survives on subsistence hunting, fishing and farming, gathering other resources they need from the forest around them.

The region has historically had to deal with illegal activity. The Bajo Amazonas sits at the nexus of Peru’s borders with both Brazil and Colombia. The boundaries of the three countries are exceptionally porous, making it difficult to track who is traveling in and out of the country and for what purpose. As a result, the forest surrounding the village has been neglected by law enforcement. Until recently, no investigation had been carried out by the national government in the area surrounding Buen Jardín de Callaru.

Because of this, crimes like deforestation — especially to make way for coca production — are rarely reported for fear of retaliation from growers and related criminal networks. This time however, the community of Buen Jardín de Callaru was determined to engage the authorities. After a community meeting, the village voted unanimously to file a denuncia —or official complaint — becoming the first indigenous community in the Bajo Amazonas region to do so.

For Garcia, the decision was a simple one. “When I saw that they had just burned our forest I said, ‘this is enough,’” Garcia said, adding, “We are the ones here in the forest.”

From Alert to Investigation

While verifying the alert, they took georeferenced photos and measurements of the area, and recorded the names of suspected culprits who had invaded from a neighboring territory. The official report was sent to the regional environmental prosecutor, the Fiscalía Especializada en Materia Ambiental (FEMA). Upon receiving the report, FEMA agreed to accompany the community to the site of the alert for an investigation.

It was December by the time the authorities were able to travel out to Buen Jardín de Callaru. Six representatives of FEMA, Peru’s special environmental prosecution, and 10 police officers hiked with the monitors to the site of the GLAD alerts in the early morning, hoping to surprise the culprit. The group was also accompanied by a documentary crew from Vice News, hoping to catch the arrests on camera. Watch the video here.

When the group arrived at the field, there was no one to catch in the act, but the monitors knew their territory and suggested traveling to a house just beyond the cleared field to confront the people likely responsible.

The FEMA prosecutors claimed that they could not investigate further at the time, because Peruvian legal protocols didn’t grant them the authority. The monitors, accompanied by Rainforest Foundation US representatives and two Peruvian environmental police, decided to go on without them. They set off down another trail through a narrow strip of forest and emerged a few moments later to find the suspect’s house standing in the middle of a vast 30-hectare sea of growing coca plants. With no back-up from the FEMA, the monitors simply had to turn away from the devastation and return home.

The Future of the Ticuna’s forest

Although there was no further government action that day, FEMA did issue a summons to the suspects for them to appear at a hearing, marking the first step towards halting further illegal activity. The area in question is now under official investigation, which could take eight months or more to complete.

While they wait, the monitors of Buen Jardin de Callaru continue to conduct patrols with GLAD deforestation alerts and satellite imagery as their guide. No further deforestation has been detected since the intervention. Garcia later told RFUS that the government action had helped, and that the coca growers had been leaving the community alone.

“We have to protect ourselves,” Garcia said.

This article was first published by our partners, Global Forest Watch. The Rainforest Foundation is using Global Forest Watch’s satellite data along with the Peruvian government’s satellite information to identify the areas the monitors investigate.