Drought Is Pushing the Amazon to the Brink: With rivers at record-low levels, wildlife struggling to survive, and hundreds of Indigenous and local communities isolated, the threat of extreme drought and rising heat is pushing the Amazon rainforest closer toward ecological collapse.

Climate change has triggered extreme drought conditions that continue to grip the Amazon in 2025.

Droughts and other climate disruptions are pushing parts of the Amazon toward a tipping point, where the rainforest fails to regenerate and begins emitting more carbon than it absorbs.

By 2050, rising temperatures, droughts, and fires could endanger nearly half of the Amazon, with far-reaching impacts for the global climate.

The droughts that gripped the Amazon in 2023 and 2024 were the most extreme on record, leaving lasting impacts that continue into 2025. In 2023, July-September rainfall across the nine Amazonian countries dropped to its lowest level in four decades. In Brazil alone, the Amazon biome lost over 8 million acres (3.3 million hectares) of surface water in 2023—an area 25 times the size of Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, the Amazon River—the world’s largest by volume, flowing through Peru, Colombia, and Brazil—saw its worst decline in water levels in over a century. The 2023 drought led the state of Amazonas in Brazil to declare a state of emergency in 95% of its municipalities, affecting more than half a million people.

Research increasingly shows that human-caused climate change is the main driver of drought in the Amazon, making extreme weather events up to 30 times more likely. Rising global temperatures have intensified drying trends, making droughts longer, more frequent, and more severe. The Amazon now receives less rainfall during the dry season (June to November) than in the past. Meanwhile, hotter temperatures accelerate evaporation from soils and vegetation, reducing moisture across the basin. Although the natural climate phenomenon El Niño contributed to recent drought conditions, its impact is minor compared to the growing effects of human-driven global warming.

Over the past 40 years, the Amazon has warmed at an average rate of 0.27 °C per decade, with some central and southeastern regions heating up as much as 0.6 °C per decade. In many of these areas, the average dry-season temperature is now more than 2 °C higher than it was 40 years ago. If current trends continue, the temperature in parts of the rainforest could rise by more than 4 °C by 2050.

Drought and deforestation interact in a vicious cycle. As drought hampers river transport, pressure has grown to pave highways like the highly contested BR‑319 in Brazil’s Amazon. But paving makes it easier to access these forested areas and accelerates deforestation, which in turn reduces rainfall by disrupting the forest’s natural water cycles (evapotranspiration). This leads to drier conditions, increased fire risk, and further forest loss. In 2023, monitoring detected more than 5,000 km of illegal side roads branching off BR‑319, intensifying the degradation of the surrounding rainforest.

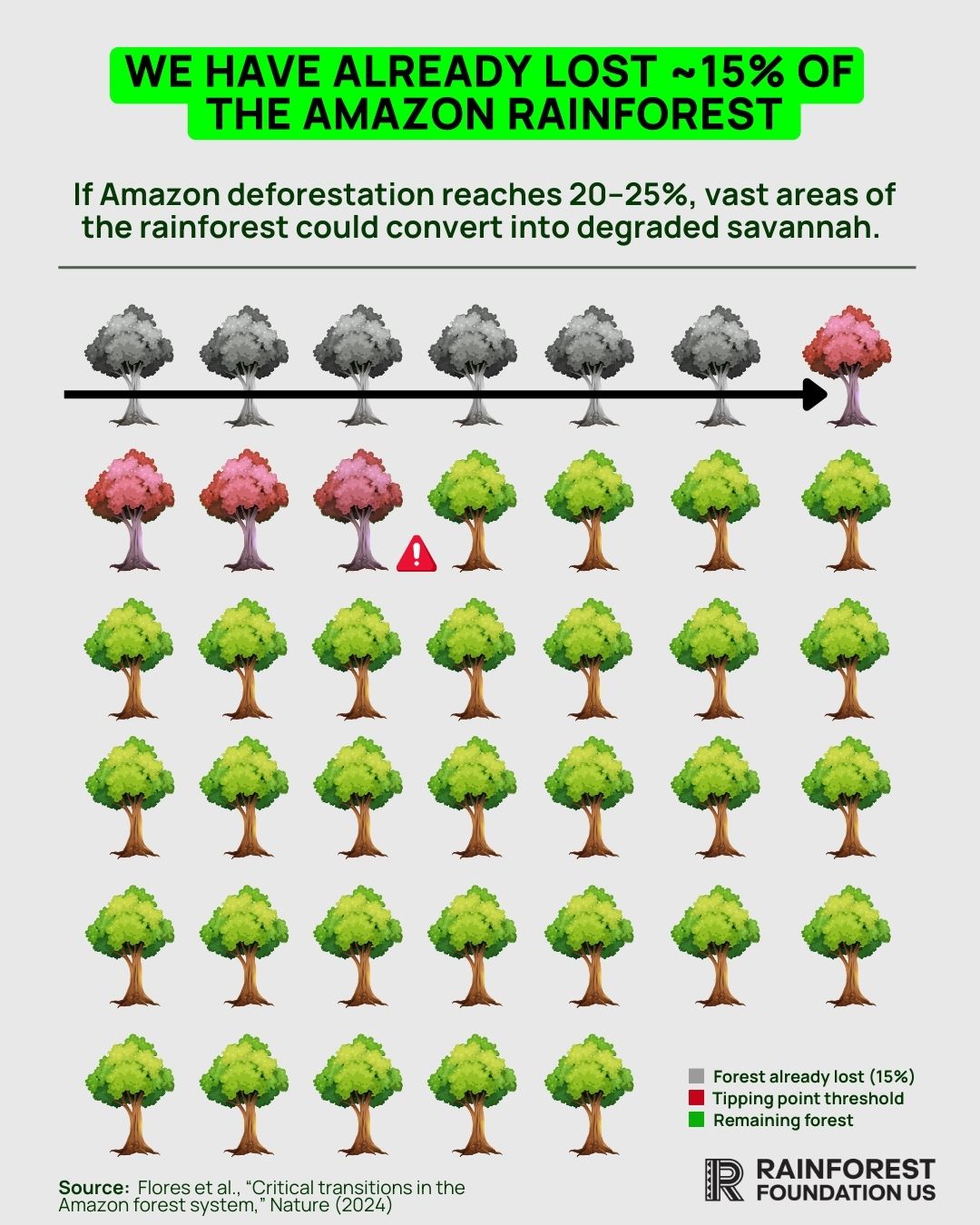

Moisture from trees in the Amazon form “flying rivers” that carry 200,000 m³ of water vapor per second across South America, feeding rainfall for crops as far away as Argentina. Losing the Amazon rainforest would cut rainfall by 40% in these regions, devastating agriculture across the continent and accelerating climate instability. Scientists warn that if deforestation reaches 20–25%, or if global temperatures climb beyond 2 °C above preindustrial levels, vast areas of the rainforest could convert into degraded savannah.

Christine Halvorson

Program Director, Rainforest Foundation US

Jhuliana Sebastian Gomez

Forest patroller and first woman leader of the San Francisco de Yahuma community, Peru

Rivers run dry: In October 2023, the Rio Negro, one of the Amazon’s largest tributaries, hit its lowest level since records began over a century ago, isolating thousands of people. Locals reported illnesses linked to drinking stagnant water. Entire riverside communities, including Indigenous people that rely on fishing and river transport, were left without access to food, medical care, or clean water.

Rivers as lifelines: In the Brazilian Amazon, over 60% of towns and villages are closer to major water bodies than to roads, underscoring their reliance on rivers as primary access routes. When waterways run dry:

Wildlife is dying: In both 2023 and 2024, overheated waters in Brazil’s Lake Tefé caused the death of over 200 endangered river dolphins and thousands of fish.

Fires are spreading: As forests dry out and pastures degrade, agricultural burns are increasingly escaping control—fueling record-breaking fire outbreaks across the Amazon. While some parts of the basin have a history of wildfires, most do not. Communities now facing fires for the first time are often unprepared for the dangers they bring.

Carbon sinks become carbon sources: Scientists warn that prolonged drought is pushing the Amazon past a critical threshold—transforming it from one of the world’s largest net carbon sinks into a carbon source. As stored carbon is released, it accelerates global climate change.

Indigenous peoples and remote rural communities are bearing the brunt of these impacts, as their livelihoods depend largely on small-scale agriculture and rivers.

Francisco Hernández Cayetano

President of FECOTYBA (Federation of Ticuna and Yahuas Communities of Bajo Amazonas)

Although scientists identify global climate change, not local deforestation, as the main driver of extreme drought in the Amazon basin, Indigenous peoples still play a crucial role in the rainforest’s resilience. They collectively hold and protect nearly one-third of rainforests in the Amazon, and securing their land rights is essential to maintaining the region’s natural water cycle. Studies show that forests inside Indigenous territories have far lower deforestation rates and less fires than surrounding areas, thereby preserving dense canopy cover that recycles vast amounts of water vapor back into the atmosphere through evapotranspiration. This process stabilizes local and regional rainfall patterns and buffers the forest against extended dry seasons.

Legal recognition of Indigenous land alone is not enough; sustained oversight and support to monitor and protect those lands are also essential. When Indigenous peoples have secure control over their territories, they protect their communities and sustain the forests and water systems that keep the Amazon alive.

Cameron Ellis

Field Science Director, Rainforest Foundation US

Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) is supporting actions that make a tangible difference in preventing and mitigating droughts. Healthy forests regulate water and climate, and Indigenous lands, when legally secured and managed, maintain denser vegetation and more consistent rainfall, buffering entire regions against drought and fires. For over 35 years, RFUS has partnered with Indigenous peoples in the Amazon to secure land rights, strengthen local governance, and provide tools and training to monitor and manage their territories.

Today, those efforts are more important than ever in supporting communities to withstand the growing threat of drought.

Without forests, we have no future. These forests sustain the lives of millions of people, stabilize our global climate, and are home to unparalleled biodiversity.

Your gift will be DOUBLED to ensure Indigenous peoples can continue defending their forests, some of Earth’s most important carbon sinks.