- A severe drought in the Amazon is disrupting transportation, isolating communities, and putting wildlife at risk for survival.

- Indigenous peoples in the region are urging their governments to declare a climate emergency.

- El Niño, deforestation, and wildfires have combined to create dire conditions.

The Amazon faces one of its most relentless droughts in recorded history. Disturbing images from Brazil’s Amazonas state show hundreds of river dolphins and countless fish dead on the riverbanks after water temperatures last week shot from 82 degrees Fahrenheit to 104 degrees Fahrenheit.

As temperatures climb, Indigenous peoples and local communities across the Central and Western Amazon—namely regions in Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Peru—are watching their rivers disappear at unprecedented rates.

“It’s a hugely worrying situation. We’ve never seen such a severe drought. As the rivers dry up, there are no fish. For the Ticuna people, the fish are our source of life.” – Francisco Hernández, leader of the Federation of the Ticuna and Yaguas Communities of the Lower Amazon (FECOTYBA), in Peru

Given the region’s dependence on waterways for transportation, the severely low river levels are disrupting the transportation of essential goods, with numerous communities struggling to access food and water. Regional health departments have warned that it is also becoming increasingly difficult to bring emergency medical assistance to many Amazonian communities.

Meanwhile, José Murayari, Vice-President of the Organization of the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Amazon (ORPIO), in Peru, says that many families are having to walk along semi-dried riverbeds for one or more miles to dig for clean water. “They can’t drink the little water that’s left because it’s too hot, and unhealthy. It’s making people sick.”

In Brazil, the state government of Amazonas has declared an emergency as authorities brace for what is already the worst drought in the state’s history, and is expected to affect the distribution of water and food to 500,000 people by the end of October. Some 20,000 children may lose access to schools.

The hot and dry conditions have also spurred wildfire across the region. Since the start of 2023, more than 11.8 million acres (18,000 sq mi) of Brazil’s Amazon have been consumed by fire, an area twice the size of Maryland. In Manaus, the capital of Amazonas in Brazil and a city of two million people, doctors have reported an increase in respiratory issues due to persistent smoke from fires, especially among children and the elderly.

Distant cities have also been impacted. In Ecuador, where normally 90% of power is generated by hydroelectric power plants, the Amazon drought has obliged the government to import energy from Colombia in order to prevent widespread power outages. “The river that flows from the Amazon, where our power plants are located, has decreased so much that hydroelectric generation was reduced to 60% on some days,” explained Fernando Santos Alvite, Ecuador’s Minister of Energy.

Though wet seasons vary throughout the Amazon, rain isn’t anticipated in most affected regions until late November or early December.

“This is a crisis — a humanitarian, environmental and health crisis, And what scares us most is what lies ahead.” – Ayan Santos Fleischmann, a hydrologist at the Mamirauá Institute in Tefé, Brazil

El Niño, Deforestation, and Fire: A Dangerous Combination

Scientists emphasize that while the extreme drought is influenced by El Niño, deforestation over the years has worsened the situation. Additionally, wildfires linked to slash-and-burn practices favored by cattle ranchers and soybean producers are pushing the region beyond its limit.

Ane Alencar, Director of Science at the Institute for Amazonian Environmental Research (IPAM), explains, “The smoke from the fires affects the rain in several ways. When you cut down native forest, you’re removing trees that release water vapor into the atmosphere, directly reducing rainfall.”

Research has shown that this degenerative process could be pushing us closer to a “tipping point” in the Amazon, with hotter and longer dry seasons potentially triggering a mass die-off of trees. A study published last year in Nature Climate Change posits that we are just decades away from vast portions of the Amazon rainforest collapsing and becoming savannah–which, in turn, would produce a devastating effect on ecosystems around the globe.

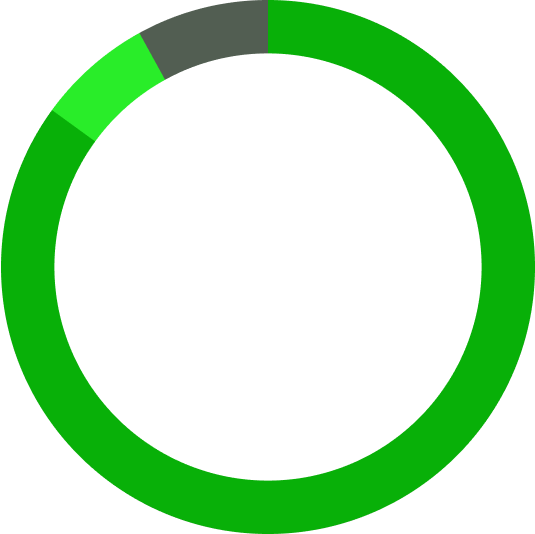

Higher water levels and lower sandbars were noted throughout the Amazon in October 2022 when compared to October 2023. These lower water levels in 2023 have resulted in massive sandbars that have disrupted transportation, isolated communities, and put wildlife at risk for survival. IMAGE CREDIT: Rainforest Foundation US

Time to Act

This drought is not an isolated natural disaster. It’s a symptom of global climate changes and the local impacts of deforestation. Tackling these challenges necessitates coordinated action on local, national, and global levels.

“We need immediate support. The Amazon river is drying up in the worst possible way, and all that’s left for our Indigenous brothers to drink is dirty water,” says Hernández.

The Brazilian government has created a task force and Peru has declared a regional emergency, but very few communities in the region have seen any coordinated effort to mitigate the impacts of the drought. Meanwhile, analysts worry that remote and isolated Indigenous communities will suffer more than most.

Indigenous peoples stand at the frontlines of climate change, despite contributing the least to greenhouse gas emissions. Now, more than ever, international solidarity and support for the affected communities are essential.