Betty Rubio Padilla, an indigenous forest patroller in Puerto Arica, Peru.

By Adam Janos and Andrea Tirado

Betty Rubio Padilla’s daughter begged her to quit her job defending the Amazon rainforest.

“She told me, ‘They can kill you. They can kidnap you.’ I know that my work is dangerous,” says Rubio, 40 years old. “But I have committed myself to this responsibility, in order to show them that nothing is impossible. So if I have to die, then I have to die. But I will die defending the forest.”

Rubio works as an indigenous forest patroller—also known within the science community as a “community monitor”. She defends over 30 square miles (7,800 hectares) of Peruvian rainforest titled to Puerto Arica, a Kichwa hamlet (population: 79) where she’s lived most of her life.

And despite her daughter’s protestations, she never neglects her family. The mother of six wakes up at 5:00 am to prepare oatmeal and chilcano—a Peruvian fish stew.

“I have to cook breakfast before I go to work. For my children,” Rubio says. “I may not come back early, depending on where I’m going.”

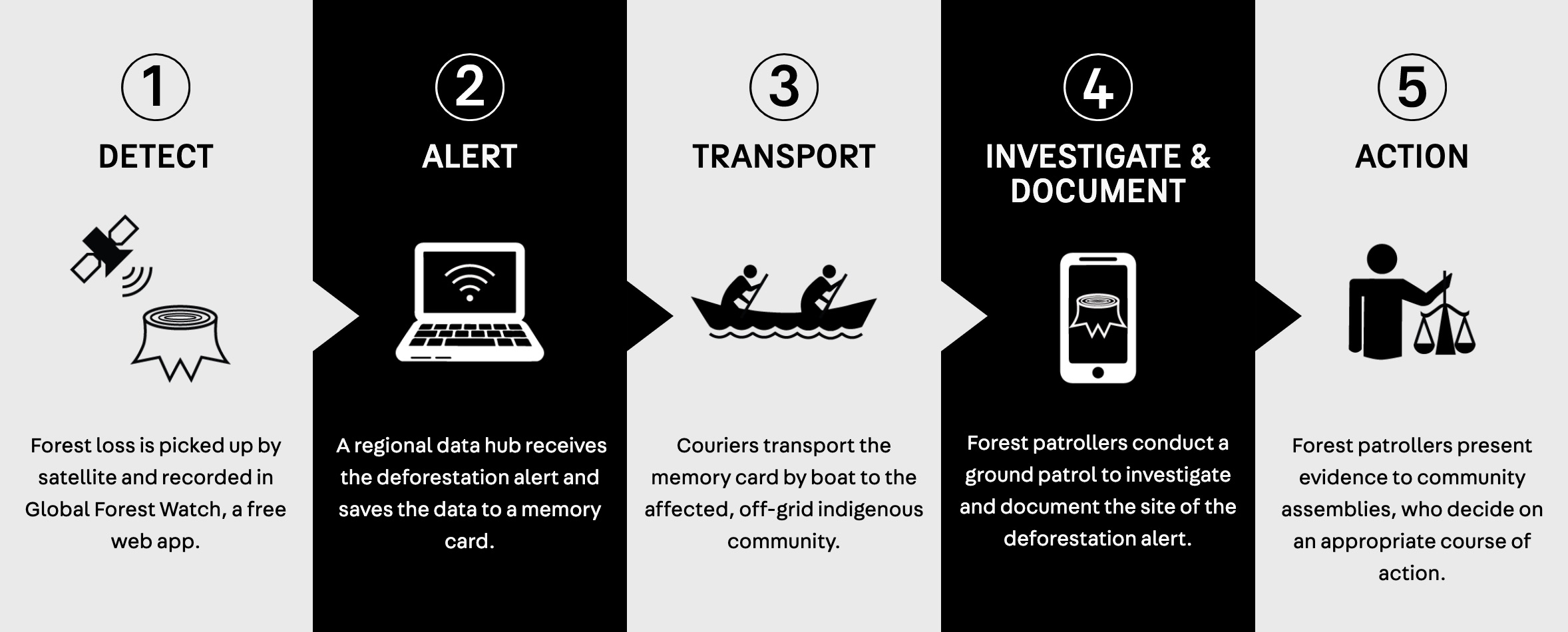

Protecting the rainforest is a complex and arduous task. Rubio reads satellite-issued deforestation alerts from her smartphone, then machetes through dense brush and wades through swamps and rivers to the correspondent GPS coordinates, where she verifies and documents tree loss. Her job is the front line of forest protection: Without these reports, Puerto Arica would be in the dark about the degradation of their land, and thus incapable of responding properly.

The work is dangerous, Rubio explains, because she’s interfering with large black-market operators. In Puerto Arica, illegal logging has run rampant. The oldest cedar and lupuna trees of Padilla’s youth have disappeared, their breathtaking trunks no longer rising up along the river banks, pilfered instead for profit.

Between 2018 and 2020, Rainforest Foundation US helped train Rubio and more than 100 other indigenous forest patrollers in Rainforest Alert, the technologies they now employ to identify deforestation on their community’s collective lands. The trainings were conducted in partnership with the Indigenous Peoples’ Organization of the Eastern Amazon (ORPIO). The territorial monitoring program is predicated on extensive scientific research, which shows that indigenous peoples are the most effective stewards of the rainforest, and that the continued health of those rainforests is crucial in the fight against climate change.

The patrol, who live and work in the northern Peruvian state of Loreto, have risen to the task. Compared to indigenous communities that didn’t utilize the technology, the tech-enabled forest patrol halved rainforest destruction in the first year of the program. That astonishing success has prompted news coverage from dozens of media outlets ranging from the BBC to France 24 to Thomson Reuters.

But for the patrollers protecting the rainforest, the work has never been about garnering international acclaim. It’s about protecting a way of life.

Francisco Hernandez, a 43-year-old forest patroller from the village of Cushillococha near the Colombian border, misses his childhood. As a young boy, Cushillococha’s eponymous lagoon was full of fish: gilded catfish, armored catfish, black prochilodus, palometa. It was a dependable bounty, from which Hernandez always ensured a meal: his belly full each night as he drifted off to sleep, a gentle breeze passing through his leaf-thatched home.

“When I was young, life was very good,” Hernandez says. But he moved to Iquitos for college, and when he returned to the 3,000 inhabitant Ticuna community of his youth, he was dismayed by the damage he saw.

Invading coca cultivators had razed large swaths of primary rainforest to tap into the promised profits of cocaine. They manufactured coca paste by the lagoon, filling the water with the chemical byproducts of their labor: gasoline, lime, sulfuric acid, bleach.

Today, the fish are gone.

“That hurt a lot,” Hernandez says, recalling his return. “I saw that my community was abandoned. I had to rescue it.”

Hernandez is committed to preserving what’s left. As a forest patroller, he monitors an immense territory. It takes two days to traverse by boat and foot. On the days he’s not patrolling he teaches six- and seven-year-olds, educating a class of 21 students on Ticuna language and traditions in a corrugated iron-roofed schoolhouse he helped construct.

Initially, not everyone in Hernandez’s community supported his forest protection work. Some saw whistleblowing on coca cultivation as allyship with the Peruvian National Police, who are scorned in the community for being the enforcement arm of an inattentive (and, at times, hostile) federal government.

“They called us informants. They said we were part of the police apparatus,” Hernandez says. Had that been true, Hernandez says, some animosity would have been justified, given the difficult history Ticuna communities have had with the national government.

“Our area has been very neglected by the state. We’ve been forgotten. They’ve never provided us with concrete support.”

But all Hernandez wants is to defend Ticuna forests. And he says the approach is working.

“We’ve reduced deforestation,” he says. “We’ve reforested [degraded land] with citrus and trees. We’ve made the people understand that their forest is the most beautiful thing we have.”

While some patrollers like Hernandez pine for the past, others are guided by a fear of a more dismal future. That’s the case with Lloyd Manuyama Peña from the Ticuna village of Bufeo Cocha.

At 27 years old, Manuyama is one of the youngest indigenous forest patrollers. He says that when he discusses the work with his male colleagues in the field they “laugh, because I am the only one who does not have a woman. I’m the only single one. I’m the only one who lives with his parents.”

But there’s one clear advantage to Manuyama’s youth: his boundless energy. Manuyama wakes up at 4:00 am for his monitoring work, criss-crosses more than 42 square miles (11,000 hectares) of viper-infested rainforests to stand up against coca cultivation, then in the afternoon travels an hour and a half by foot to his university in Caballococha, where he studies philosophy and psychopedagogy until 8:00 pm at night.

Like the others, Manuyama is unwavering in his commitment to forest protection. During the first wave of COVID-19, he fell ill alongside everyone in his household: his mother, father, 22-year-old sister, and her infant daughter. But taking a break was not an option: The other local forest patrollers were sick as well. So Manuyama continued to work his shifts, treating his shortness of breath and deep fatigue with homeopathic remedies, the only medicine at his disposal: cooked ginger, honey, lemongrass, abuta.

On one shift, battered by illness and exposed to a continuous downpour, Manuyama recalls that “I almost fainted on the side of the mountain. It was difficult to walk. My weakness grabbed hold of me.”

But for all that discomfort, Manuyama has no regrets about taking on his challenge. The stakes feel too high when he thinks about the future awaiting the youngest of the young: people like his one-year-old niece whom he shares a bedroom with.

“I want future generations to know what a cedar tree is, what a chestnut tree is, what a paiche is… the children are going to be stuck with what we leave behind.”

And he’s optimistic that the monitoring work can help leave behind a brighter tomorrow.

“As soon as this monitoring work began, the deforestation of our territory was paralyzed.”

As for Rubio, she hopes to do more than protecting the forest. She aspires to be a role model to women, so that the guardians of the rainforest might diversify as they grow in number.

“Many women were not as easily able to get this opportunity as I was,” she says, explaining that a lot of women feel pressured to not pursue the work because they feel they must remain tethered to their domiciles. “But I can tell other women: that as women, we are not incapable… I share my experience with other women in the community, so they can make a decision. They can say: “Yes, I will do it. Just like you have.’”