- Indigenous communities are building a bold new strategy for climate adaptation and fire prevention in the Amazon.

- At a recent gathering in Peru, Indigenous peoples came together to share strategies, strengthen resilience, and call for direct access to climate finance.

- They are combining ancestral knowledge with modern tools like drones and real-time monitoring to protect their territories from the deepening impacts of climate change.

A bold strategy is emerging in response to the escalating threats of fire and drought in the Amazon. Shaped by those who know the forest best, Indigenous peoples are forging their own path, leading climate adaptation efforts rooted in ancestral knowledge, territorial defense, and collective survival. From the territories, for the territories, this plan is driven by a vision for a future that does not burn.

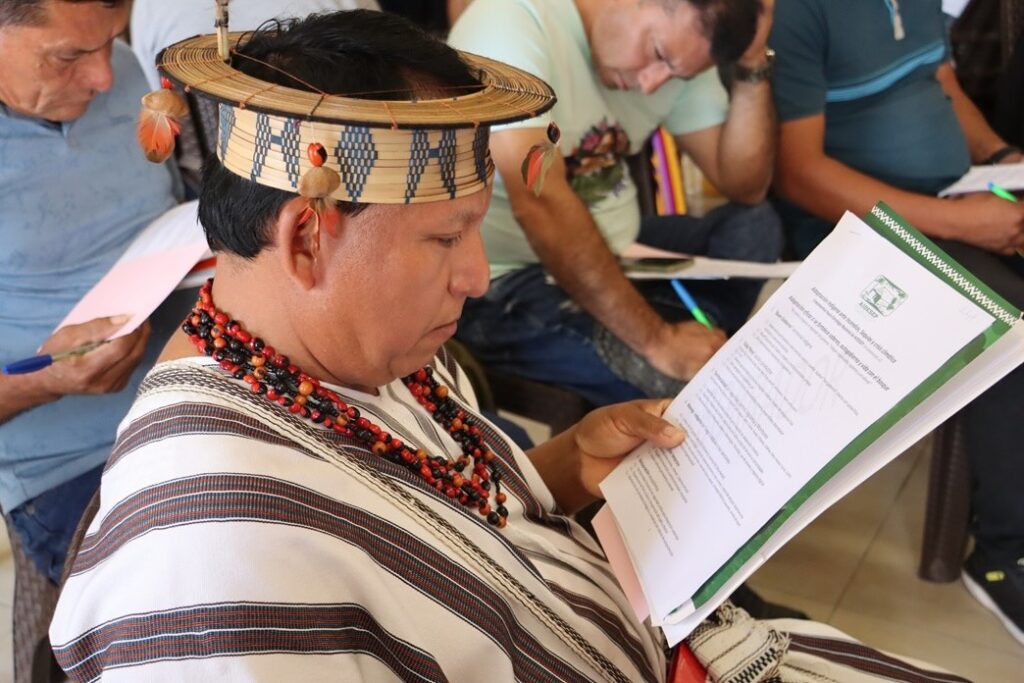

Last month, delegations from more than eight Indigenous peoples—including the Kichwa, Ticuna, and Wampís—gathered in Moyobamba, northern Peru, to exchange knowledge and co-create a climate adaptation strategy. Organized by Rainforest Foundation US’s (RFUS) partner, the Inter-Ethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP), the gathering brought together Indigenous women leaders, technical experts, and territorial organizations. Discussions focused on urgent priorities: preventing and controlling fires, strengthening territorial governance, advancing Indigenous-led economies, and securing direct access to climate finance. The gathering concluded with a concrete step forward: a draft National Strategy for Indigenous Adaptation to Fires, Droughts, and the Climate Crisis.

Sharing Knowledge for Collective Resilience

During the three-day gathering in Moyobamba, participants shared firsthand accounts of the deep toll these crises are taking on their lands, livelihoods, and cultures. Communities described how the very nature of fire is changing, as longer, dryer summers decrease the humid forest’s natural defenses against flames. Traditional signs—the moon, the wind, the rain, the behavior of animals—once used to anticipate and prepare for fire season, are no longer reliable.

Participants also raised alarm over the impact of prolonged drought on ancestral practices like controlled burns. Long used as a tool for sustainable land management, these carefully timed burns have become more difficult and dangerous to carry out. In fire-adapted regions, controlled burns keep flames lower and slower by clearing the brush that allows fire to climb into the canopy, where it spreads more easily.

Delegates from Kichwa territories, with deeper experience managing fire, shared these practices with the Ticuna and other groups who have had less exposure but now face heightened vulnerability as climate change reshapes their forests.

Participants also discussed how to adapt monitoring strategies to protect their territories from natural disaster. In the Ticuna community of Buen Jardín del Callaru, fires broke out near the border of a neighboring area. Forest patrollers responded swiftly, using tools from RFUS’s Rainforest Alert program, including drones, smartphones, and real-time monitoring technology, to assess the threat and coordinate a rapid response. Community members dug firebreaks and used fumigation pumps filled with water to suppress the flames.

For us, exchanging knowledge among different communities and Indigenous peoples is essential. Each community has their own perspective, way of thinking, and way of living. By sharing and communicating, we can prevent large-scale damage from fires and droughts.

– Francisco Hernández Cayetano, President of the Federation of Ticuna and Yahuas Communities of Bajo Amazonas (FECOTYBA)

Throughout the multiday event, Indigenous women were at the heart of the dialogue. Uziela Achayap, an Awajún leader, shared how women in her community are restoring forests, protecting native seeds, and sustainably managing chacras—the traditional gardens that are vital to land revitalization, food sovereignty, and climate resilience. “The participation of Indigenous women is fundamental because they are active leaders in defending territory and life. Their role goes beyond preserving knowledge; they drive concrete solutions in the face of the climate crisis,” affirmed a member of the AIDESEP Communications team.

La Vida Plena: An Indigenous Vision for Climate Adaptation

At the core of the National Strategy for Indigenous Adaptation to Fires, Droughts, and the Climate Crisis is the shared vision for La Vida Plena (The Full Life), a future guided by community-defined rules that prioritize collective well-being and ecological balance.

The plan weaves together monitoring tools like GPS mapping and radio communication with ancestral knowledge to create early warning systems for fire. It calls for restoring degraded lands through Indigenous-led fire and drought management, enforcing community protocols, and interpreting forest signals to anticipate climate threats. Central to the strategy is the training and equipping of community fire brigades, with strong participation from women and youth, and the strengthening of Indigenous leadership across generations.

One of the biggest obstacles facing Indigenous climate adaptation efforts is the lack of meaningful support from national, regional, and local governments, alongside limited and often inaccessible climate finance. “Without resources, we cannot safeguard our forests properly. There must always be support, from the government, from the world, so that our forests remain standing [and] so the Amazon continues to provide water and fish that sustain Indigenous populations,” said Cayetano. In response, Indigenous leaders are calling for climate finance mechanisms that deliver funding directly to the territories where it’s needed most.

To support Indigenous led climate adaptation, RFUS supports Indigenous partners through territorial monitoring and direct funding mechanisms. Through the Rainforest Alert program, Indigenous forest patrollers receive the tools, training, and technology they need to monitor their lands, detect illegal activity, and now, respond to fires. RFUS also works to strengthen Indigenous organizations’ governance and administrative systems, ensuring they can access, manage, and scale direct climate finance on their own terms.

No one protects tropical forests more effectively than Indigenous peoples, yet they receive only a fraction of climate funding. That’s why we provide funding directly to their organizations while strengthening the institutional capacity of our partners so that they can access large grants and manage them autonomously over the long term.

– Victor Gil, Capacity Strengthening Senior Manager at Rainforest Foundation US

First to Face Fire

Fires and drought in the Amazon rainforest may feel distant for city-dwellers, but their consequences are anything but. In 2024, Brazil and Peru faced some of their worst fire seasons on record. For the first time, fires, not agriculture, became the region’s leading cause of forest loss1. Forest fires now destroy more than twice as much tree cover annually as they did just two decades ago2, and prolonged drought has turned vast areas into tinderboxes, fueling larger, hotter, more frequent, and more devastating blazes.

Fires release vast amounts of carbon stored in trees and soil, fueling a vicious cycle: rising temperatures drive more fires, and fires accelerate climate change, pushing the world’s largest rainforest from a vital carbon sink toward becoming a dangerous carbon source.

As these crises intensify the global climate emergency, it is Indigenous peoples, whose ancestral lands lie within the forest, who are bearing the brunt of the damage, standing on the frontlines of a crisis they did not create.

Last year [2024] was extremely dry. There was no water, and what little remained was dirty. The fish in the river died. The drought lasted nearly five months, from July to November. It wasn’t like this before. We’ve been suffering for the last two years, and they say this year will be even worse.

— Jhuliana Sebastian Gomez, Forest patroller and first female leader of the San Francisco de Yahuma community, Peru

From Moyobamba to the World

The closing session in Moyobamba underscored a shared commitment to advance Indigenous-led adaptation strategy built from the ground up. Protecting forests, sustaining cultures and livelihoods, and preserving ancestral knowledge all depend on placing Indigenous leadership at the center of climate action. The delegations will now bring the insights and proposals shared in Moyobamba back to their communities for reflection, validation, and implementation, ensuring these collective strategies continue to grow and adapt to a changing climate.

I believe that governments, NGOs, and the international community must focus more on the Amazon. I am concerned that the Amazon is disappearing…We need to safeguard our forests so that in 10 years, we can restore the forest’s dynamics and maintain healthy ecosystems for our children, youth, and all peoples

– Francisco Hernández Cayetano, President of FECOTYBA

As Indigenous peoples prepare for COP30, set to take place later this year in Belém, Brazil, they are working together to share the knowledge that sustains both their communities and our collective survival. The question now is whether world leaders are ready to recognize the solutions that already exist, while the forest is still standing.

Sources:

- World Resources Institute, The Latest Data Confirms: Forest Fires Are Getting Worse, July 21, 2025 ↩︎

- World Resources Institute, The Latest Data Confirms: Forest Fires Are Getting Worse, July 21, 2025 ↩︎