Forest Patrol Instructor Mirian Sanchez explains tech-based forest protection to the women of San Jose de Pacache in Peru.

Editor’s Note: Rainforest Foundation US’s standard editorial policy is to withhold children’s names. With parental consent, an exception was made for this story.

When Mirian Sanchez arrives at the dock of San Jose de Pacache in the Peruvian Amazon, the villagers are already waiting for her. Middle-aged indigenous Shipibo women in electric blue blouses and knitted skirts take her by the elbow and assertively maneuver her into the back of a motorcycle rickshaw, which bounces down a dirt road towards the village, kicking up clouds of red earth.

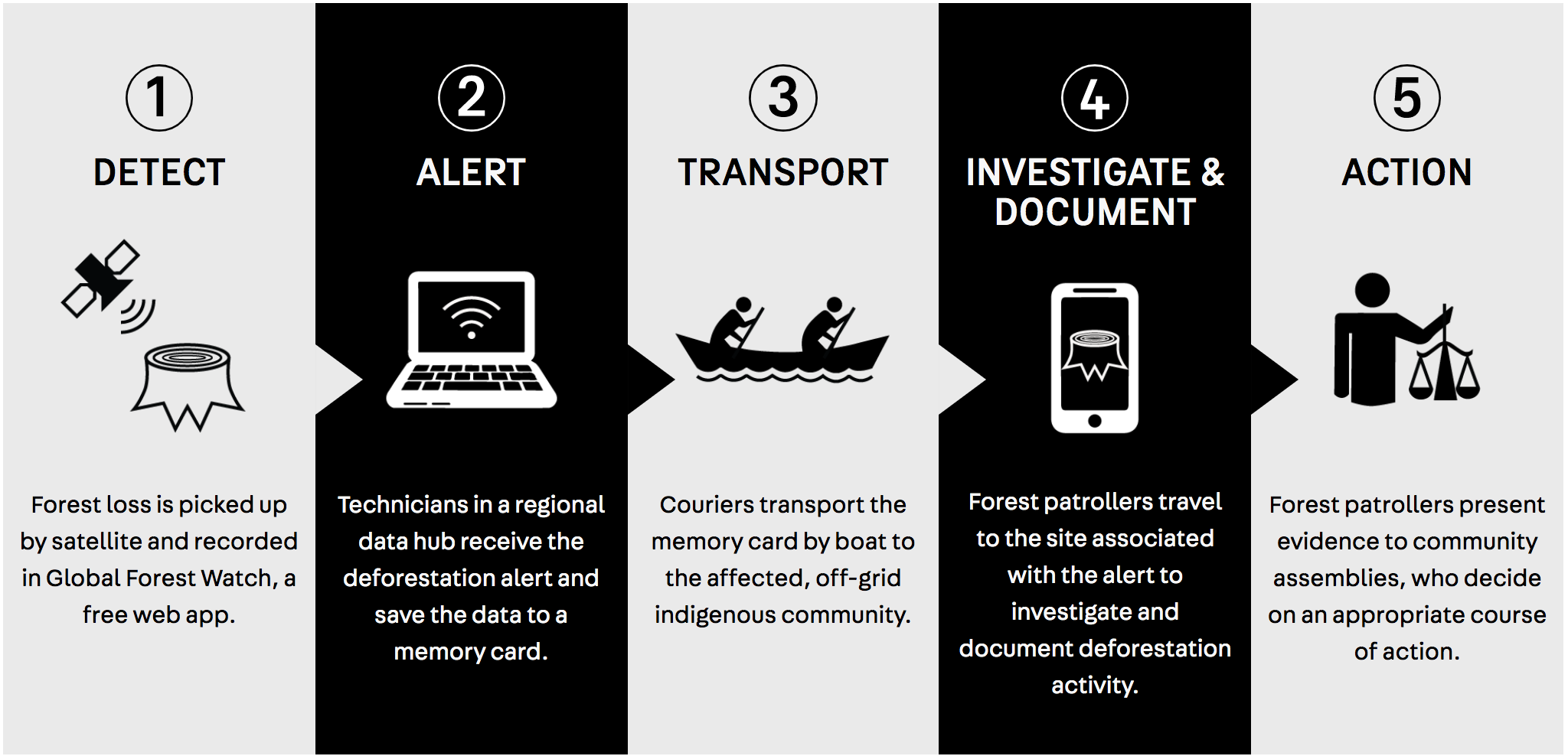

Sanchez, a Shipibo herself, is from Puerto Nuevo three hours away, and she works as a forest patrol instructor for the Regional Organization of AIDESEP in Ucayali (ORAU) and Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS). Based in the Peruvian department of Ucayali in the Peruvian Amazon, she has come to San Jose de Pacache to introduce the villagers to Rainforest Alert—the indigenous-led forest patrol program (also known as “community monitoring”) co-designed by the Organization of the Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Amazon (ORPIO) and RFUS. In the program, forest patrollers receive satellite deforestation data on their smartphones, allowing them to quickly respond when invaders are cutting down their trees.

The Rainforest Alert program has shown astounding initial results, with one peer-reviewed study suggesting that the forest protection system can reduce deforestation by more than 50% in a single year.

Sanchez, 35 years old, presents the program in the village’s communal gathering place—a faded blue wooden building with a dirt floor, where dozens of villagers have crammed together on a hodge-podge of wooden benches and plastic stools. Together, they suffer the brutal heat of the midday sun to watch her explain the system on a taped-up print-out of their village’s territorial map.

The forest patrollers rely on smartphones, Sanchez explains. They go to the points of presumed deforestation and document evidence with cameras and drones. It can be hard explaining these things to a village so off-the-grid that they have no running water or permanent power source (let alone smartphones or internet). But Sanchez uses workaday language, switching deftly between Shipibo and Spanish so everyone in the multilingual community understands.

“In my day to day, I spend more time speaking Spanish,” Sanchez says. “But I’m Shipibo. I still dream in Shipibo.”

Sanchez was chosen for her role as an instructor as part of a larger gender-inclusion effort by RFUS, in response to calls by regional and international indigenous women leaders to elevate their counterparts in territorial governance decision-making. In 2021, RFUS supported the Summit of Indigenous Women of the Amazon Basin, which called for increased “support to women in the management, care, and development of the territory.” A recent grant to RFUS provided by the United States Agency for International Development will similarly strengthen the Women’s Coordination network under the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests (AMPB), the representative indigenous peoples’ and local community organization in Central America.

Too often, indigenous women have unequal access to income, education, and professional opportunities, leaving them out of the equation when it comes to solving the climate crisis. In the first expansion of Rainforest Alert, the work force was overwhelmingly male: 116 of 120 forest patrollers were men.

“Reducing the gender disparity in the forest patrol program isn’t just about heralding women’s rights,” says Wendy Pineda, Program Coordinator for RFUS in Peru. “By bringing more women into leadership roles the talent pool of prospective forest patrollers doubles, ensuring that the best people possible end up in these positions.”

“Plus,” Pineda says, “There’s a logic to elevating the most qualified indigenous women into educator positions. It’s a role they play, de facto.”

“They’re the ones teaching their children at home,” Pineda says. “They’re teaching them about the environment and about how to respect the forest. If we’re going to keep protecting these rainforests, we need to respect the knowledge these women bring.”

But there’s more to elevating women than simply offering them jobs—the women need to accept. And that’s been a hard sell.

“We went to numerous assemblies in numerous villages. We begged them. We said: Please pick a woman. And none of them could give us one,” Pineda says.

In an attempt to approach the issue, RFUS staff in Peru conducted focus groups with indigenous women, asking them what was preventing them from joining the forest patrol. In those focus groups, RFUS learned that many women felt unable because of the gendered expectation in their homes and communities that they would take care of their children—professional development workshops were oppositional to that domestic duty. In response, RFUS helped establish temporary daycare centers in villages where forest patrollers were being trained, so that more women could take the first step to participation.

The system opened the door for more women to apply. As a result, women like Evelith Noteno stepped forward into an opportunity that allows her to earn her livelihood defending the rainforest.

Only 19 years old, Noteno is the youngest forest patrol instructor, having recently been promoted from her position as a patroller. Her daughter is an infant, and when Noteno first began patrolling the rainforest around her Kichwa village of Monterrico, her daughter was only one month old.

“It’s a beautiful experience,” Noteno says. “I like going to the villages and teaching people. It’s important to empower other women. The majority of people say, ‘Only men can do this.’ But it’s important to show them: We can do the same work.”

Noteno adds that the program has ignited in her an aspiration to become an engineer, and she hopes that her experience as a patroller can develop those skills, allowing her to advance further in a career of technology-based environmental conservation.

Back in San Jose de Pacache, Sanchez instructs the assembled villagers to form two breakout groups. The community instinctively divides along gender lines, with the men and women clumping on opposite sides of the room. Over the next phase of the training, they will learn the whole Rainforest Alert program: how to use the smartphones to read satellite maps and deforestation alerts, and how to set up and fly drones.

The men stay in the communal lounge with an RFUS technician to learn how to navigate smartphones and the app that they use to geo-reference suspected deforestation. The women head outside with Sanchez, where she sets up the drone in the center of a soccer pitch.

“I like this work,” Sanchez says. “I’m good at it. Some people are afraid. They feel embarrassed—they think it’ll be too hard, and they’ll look stupid. But it’s easy. It’s just a matter of practice.”

As she launches the drone skyward, the crowd of women gasps. Amongst them stands a young girl: Sanchez’s 10-year-old daughter, Abigail, who has happily joined her mother at work today. Abigail grins at the villagers’ astonishment. For her, this is old news.

“I like going into the forest with my mom,” Abigail says of the work. “And I love playing with the drone.”

“You’re never allowed to operate the drone,” Sanchez corrects.

“Well, not yet,” Abigail says. “But one day I’ll be an engineer. And then, I think, I’ll be allowed.”