Aerial view of the Yanomami Indigenous people’s territory in Roraima, Brazil.

IMAGE CREDIT: Christine Halvorson/Rainforest Foundation US

- The government’s removal of invaders may have been a decisive factor in decreasing deforestation.

- Despite the good news, the state of Roraima suffered the majority of damage due to wildfires.

- Land titling allows Indigenous peoples to manage their lands in ways that protect biodiversity.

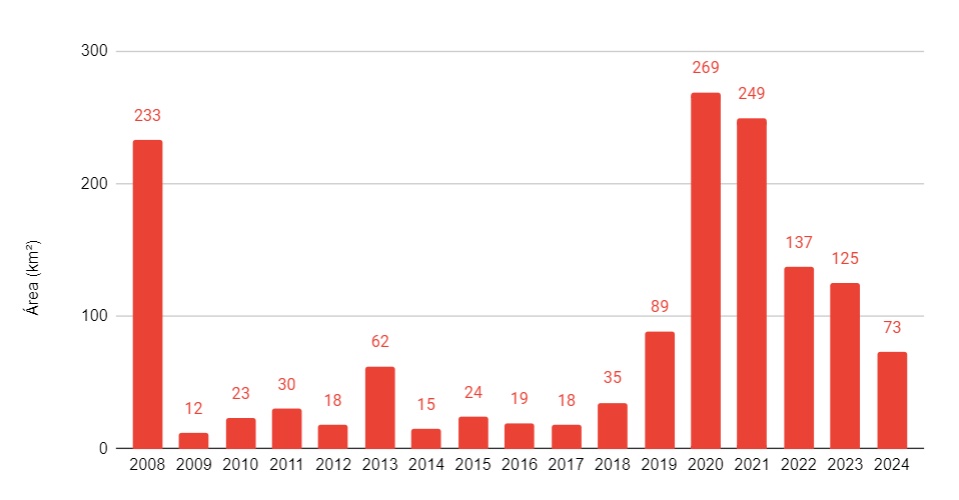

Indigenous peoples’ lands in the Amazon experienced a 42% decrease in deforestation between August 2023 and March 2024, according to a report by the Brazilian organization Amazon Institute of People and the Environment (Imazon). This is the lowest amount of destruction recorded within these territories since 2018.

The Apyterewa Indigenous land in Brazil’s Eastern Pará state, which had been the most deforested in the Amazon for four consecutive years, has not appeared in the ranking of the most deforested areas for four months due to the removal of criminals by federal authorities. Home of the Parakanã people, Apyterewa lost over 80,000 acres of forest in the last four years, an area approximately the size of Portland, Oregon.

Meanwhile, the state of Roraima experienced the most significant devastation across its territories, with the Indigenous Moskou territory most affected by illegal deforestation in the same period. Severe drought in the region has also left forests increasingly susceptible to wildfires, a major factor contributing to environmental degradation.

According to the National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Roraima witnessed 4,481 fires in the first four months of this year (from January 1 to April 14)—an increase of 285% compared to the same period in 2023 due to several factors, including deforestation and fires set by criminals. The state accounted for almost 30% of Brazil’s fires.

The vulnerability of Indigenous communities is further highlighted by the plight of the Indigenous Anzol community, which was left out of a regional land titling process and suffered more because of it, as reported by Sumaúma news outlet. The lack of territorial security means Anzol’s residents lack access to natural water sources and forest. They survive through subsistence agriculture, growing bananas and cassava in small areas of around 1,500 square meters and raising small animals, like pigs and chickens, so they had to buy food in the city. To make matters worse, the community lost their cassava harvest in the recent fires, putting their way of life at risk.

In the national context of Indigenous peoples’ land rights, Lula’s administration has faltered in its commitment to uphold these rights. Despite promising to title 14 Indigenous territories in the first 100 days of his presidency, only ten territories have been officially recognized since he took office on January 1, 2023. Twenty-six other titles are still awaiting final government approval, leaving dozens of Indigenous communities vulnerable.

“To sustain the current decline in deforestation and ensure the ongoing protection of Indigenous peoples, it is imperative for the Brazilian government to expedite the titling of lands and the expulsion of invaders from Indigenous territories. These lands are crucial buffers against deforestation, making their protection a top priority,” said Christine Halvorson, Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) Program Director. “Land titling is critical because it gives Indigenous communities legal recognition, essential for protecting their territories from deforestation and encroachment. This legal security allows them to manage their lands in ways that protect the forest’s biodiversity, contributing significantly to the fight against the climate crisis by maintaining carbon sinks and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.”

RFUS will continue working in hard-hit Roraima, in collaboration with its partners—the Indigenous Council of Roraima (CIR), two Wai Wai organizations (AIWA and APIWX), and the Wanasseduume Ye’kwana Association—to support Indigenous communities in securing the legal recognition and titling of their lands.