Para leer esta historia en español, haga clic aquí.

- Peru and Brazil’s Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Corridors contain the world’s largest contiguous territories of Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation.

- Illegal logging, coca cultivation, and extractive industries are rapidly advancing into these corridors—putting Indigenous communities and ecosystems under serious threat.

- Indigenous organizations in Peru and Brazil are spearheading a cross-border effort to secure permanent protection for these vital corridors.

Deep in the remote borderlands of the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon rainforest, hidden within an expanse of towering trees, lie the world’s largest contiguous territories of Indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation. These remote borderlands are home to two critical lifelines of the Amazon—the Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Territorial Corridors. Within these corridors, jaguars and pumas prowl beneath the canopy, their survival intertwined with that of the Indigenous peoples who share this land. These corridors are among the planet’s last great strongholds of biodiversity, their resilience a direct result of centuries of Indigenous stewardship. But as threats continue to eat away at the corridors’ edges, the fate of these forests—and the people who have protected them for generations—is deeply uncertain.

Both Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation and the recently contacted ‘buffer-zone’ communities living along the corridor’s edges are facing mounting threats—from illegal criminal networks to extractive industries that push deeper into the forest each day. In response, Indigenous organizations in Peru and Brazil are leading the fight to secure permanent protection for the Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Territorial Corridors, ensuring that the rights of Indigenous peoples are not only recognized but actively upheld. Securing Indigenous peoples’ land rights and respecting the choice of these communities to remain in isolation is more than a human rights imperative—it is a last line of defense for the Amazon itself, a safeguard for one of Earth’s greatest climate stabilizers. At stake is nothing less than the survival of the rainforest, and with it, the future of our planet.

The Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Territorial Corridors

Spanning over 39 million acres—an area more than twice the size of Panama—the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor is named after the two rivers that weave through its vast expanse. On the Brazilian side, 21 million acres—54% of the corridor’s total area—are formally designated as Indigenous lands1. This includes the Vale do Javari Indigenous Territory, the second-largest Indigenous reserve in Brazil. In Peru, 7 million acres—18% of the total corridor—are recognized as Native Communities and Indigenous Reserves specifically set aside to protect Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation, including in the Matsés National Reserve1. Together, these territories form the backbone of the corridors’ protection.

The Pano Arawak Territorial Corridor covers 22 million acres—an area roughly the size of South Carolina. This vast territory is a critical stronghold for isolated Indigenous peoples and is home to at least six identified and four yet unidentified Indigenous groups living in voluntary isolation. In Peru, four official reserves—Murunahua, Mashco Piro, Madre de Dios, and Kugapakori-Nahua-Nanti—are designated to protect isolated groups, with the latter two recognized as “Territorial Reserves” under Peru’s PIACI (Indigenous Peoples in Isolation and Initial Contact) Law. On the Brazilian side, the state of Acre is home to 24% of all known Indigenous groups living in isolation, totaling six distinct communities.

A Critical Refuge for Biodiversity

These corridors are among the most biodiverse stretches of rainforest left on Earth. Beyond sheltering an extraordinary wealth of species, the corridors play a critical role in stabilizing the global climate—potentially storing a staggering 13.7 billion tonnes of CO2, more than twice the total annual emissions of the United States.

Safeguarding these territories means protecting irreplaceable ecosystems and preserving one of the planet’s most powerful carbon reserves. With 95% of the forest in these two corridors still standing, they represent a haven for biodiversity and one of the last and greatest natural defenses we have against climate collapse.

– Wendy Pineda, General Project Manager at Rainforest Foundation US

The Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor is known for harboring the world’s greatest diversity of apex predators, such as pumas and near-threatened jaguars, which require vast, undisturbed territories to survive. It is also home to rare and threatened species such as the giant anteater and the giant armadillo. The corridor’s waterways are teeming with aquatic mammals, including the Amazon river dolphin and the tucuxi dolphin, while the giant otter, a species increasingly rare in other parts of the Amazon, remains well protected within these lands. This extraordinary biodiversity exists because of generations of Indigenous stewardship and knowledge of the lands. The Matsés people, for instance, have identified and classified over 47 distinct habitat types within their lands—an intricate knowledge system that has sustained both their way of life and the delicate ecological balance of this corridor.

Encroaching Threats

Although both Peru and Brazil have laws that explicitly prohibit contact with Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation, dangerous encounters with loggers, missionaries, and criminal organizations tied to drug and wildlife trafficking are becoming alarmingly frequent. And while national parks, reserves, and formally recognized Indigenous lands exist within both corridors, vast stretches remain unprotected. These unprotected stretches are easy targets for extractive industries and criminal networks that operate with impunity, tightening their grip on the heart of the Amazon.

“The Peruvian and Brazilian governments are granting rights to exploit natural resources within the territories of Indigenous peoples living in isolation and initial contact,” said Beatriz Huertas, Isolated Peoples Policy Senior Adviser at Rainforest Foundation Norway. “Across the corridors—especially in areas where Indigenous reserves have been requested—there is mounting pressure to open these lands to resource extraction. This represents a threat of enormous proportions.”

In the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor a growing crisis of wildlife exploitation is unfolding. Cities bordering the corridor have a high demand for fish (primarily pirarucu, a large air-breathing freshwater fish), wild game, and turtles, fueling large-scale poaching. This trade is embedded in a long-standing cross-border network, with an estimated 278 tons of game meat trafficked annually1. Mass turtle poaching is rampant, with seized canoes carrying up to 700 illegally captured turtles. Without stronger protections and enforcement, these extractive pressures will continue to erode the ecological and cultural integrity of these corridors.

Infrastructure projects, particularly roads, are accelerating this crisis, carving pathways to access the remote reaches of Indigenous peoples’ lands. While deforestation in the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor remains relatively low for now, proposed road construction projects—backed by regional governments on both sides of the border threaten these corridors. Beyond opening a direct gateway for criminal networks and accelerating deforestation, these projects escalate violence, ignite conflict, and expose communities to life-threatening diseases, putting both Indigenous peoples’ lives and their forests at even greater risk. Meanwhile, in both Brazil and Peru, lawmakers are pushing proposals that further threaten Indigenous peoples’ lands. In Peru, a recent amendment to the Forestry and Wildlife Law removes the need for state approval to convert forested lands to other uses, paving the way for accelerated deforestation and land grabs—without the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous communities. This rollback not only erodes Indigenous peoples’ rights but also erodes environmental protections, opening the door to even greater destruction.

Many Indigenous communities will be deeply impacted by Peru’s changing legislation. Invaders are likely to seize on these legal changes to expand their control over larger areas of land for a range of purposes—including coca cultivation linked to drug trafficking, as well as the expansion of monocultures like palm oil and other extractive industries.

– Beatriz Huertas, Isolated Peoples Policy Senior Adviser at Rainforest Foundation Norway

A Cross-Border Effort for Protection

Recognizing the urgency, Indigenous organizations in Peru and Brazil have joined forces and are leading the fight to secure permanent protection for the Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Territorial Corridors. At the core of this fight lies Indigenous peoples’ fundamental right to their ancestral lands. Without legal recognition and secure, community-held land titles, Indigenous peoples cannot fully assert their rights to protect their forests. Ensuring formal land tenure is not just a legal necessity—it is an essential step toward protecting one of the last intact strongholds for Indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation.

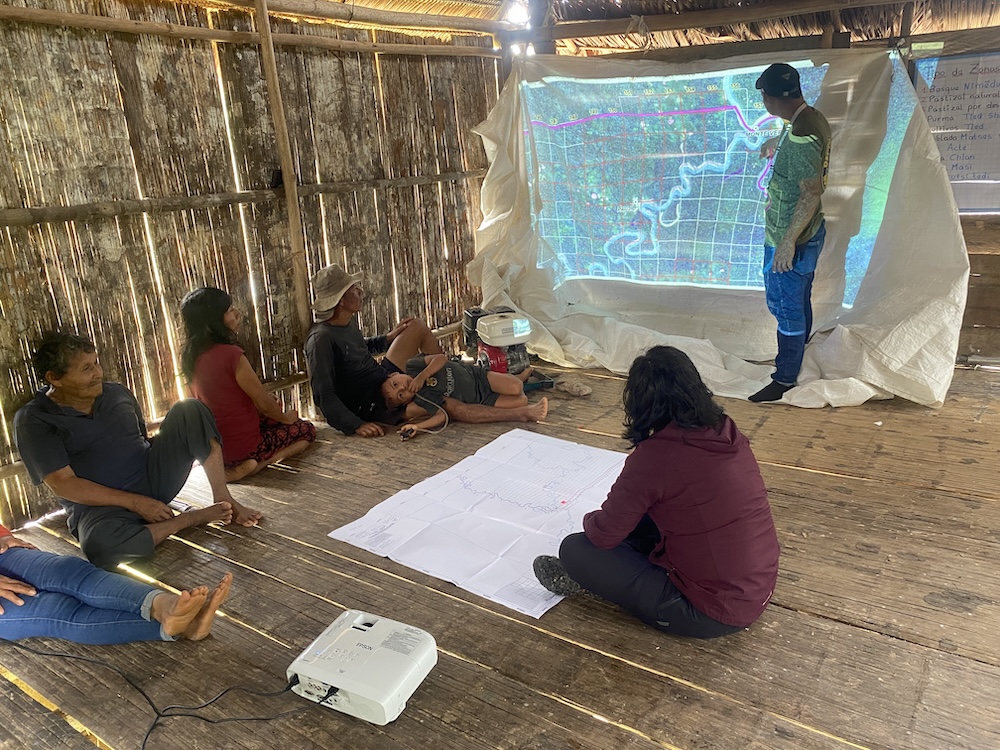

This effort involves hundreds of Indigenous organizations, local communities, civil society groups, and government entities, working together and advocating for the creation of isolated peoples’ reserves, land titling, and land security. A bi-national platform of Indigenous organizations has also been established to coordinate and drive the implementation of the territorial corridor protection plan. A key strategy is supporting Indigenous communities in the ‘buffer zones’. These frontline communities play a vital role as guardians of the corridor’s edges, acting as the first line of defense against the encroaching threats. To strengthen their ability to protect these lands, communities in the buffer zones must be equipped with technological tools, training, and capacity-building initiatives that enable them to monitor, document, and respond to illegal activities. However, technology alone is not enough—these efforts must be embedded within broader Indigenous governance strategies and sustainable livelihood protections to ensure long-term resilience.

Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS), in collaboration with the Interethnic Association for the Development of the Peruvian Rainforest (AIDESEP) and the Organization of Indigenous Peoples of the Eastern Amazon (ORPIO), has a significant opportunity to support Indigenous communities in securing community-held land titles and land title extensions in Peru. AIDESEP has identified 181 Indigenous communities in Loreto that span over 8 million acres that still lack legal title to their lands. Many of these communities are strategically located, adjoining or controlling key access points to protected areas and the Yavarí-Tapiche Territorial Corridor.

The Clock is Ticking

Protecting healthy rainforests is essential to combat both climate breakdown and biodiversity loss. Studies demonstrate that Indigenous peoples are the rainforests’ best defenders with lower deforestation rates and higher carbon capture on their lands compared to other types of protected areas, including national parks.

Securing protection for these two corridors is no easy task. They span two nations with different histories, political systems, and legal frameworks—demanding strategic coordination, tough negotiations, and constant resistance against powerful economic interests. Without swift and united action, these Indigenous territories will be left increasingly vulnerable to outside pressures.

– Christine Halvorson, Program Director at RFUS

Securing Indigenous peoples’ land rights in and around the Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Territorial Corridors will reinforce a stronger barrier against illegal activities and deliver substantial contributions to international climate and biodiversity targets, including the 30×30 agenda and the COP26 pledge to end deforestation by 2030.

Honoring the choice of Indigenous peoples to live in voluntary isolation—and ensuring that Indigenous communities within these corridors and beyond can live with dignity, with their cultures, health, and livelihoods safeguarded—is not just a matter of justice, but a necessity for the Amazon’s survival. Equipped with the rights, tools, and protections they need to defend their lands, these communities are the Amazon’s strongest line of defense—ensuring that its forests, and the life they sustain, endure for generations to come.

Learn more about Indigenous-led rainforest protection and keep up with the latest developments in our work by signing up for our email list today.

Partners and Organizations Leading the Protection of the Yavarí-Tapiche and Pano Arawak Territorial Corridors:

Organización Regional de Pueblos Indígenas del Oriente (ORPIO), Organización Regional de AIDESEP-Ucayali (ORAU), Federación Nativa del Río Madre de Dios (FENAMAD), Asociación Interétnica de Desarrollo de la Selva Peruana (AIDESEP), União dos Povos Indígenas do Vale do Javari (UNIVAJA), Organização dos Povos Indígenas do Rio Juruá (OPIRJ), Associação Ashaninka do Rio Amônia (APIWTXA), Coordenação das Organizações Indígenas da Amazônia Brasileira (COIAB), Observatório dos Direitos Humanos dos Povos Indígenas Isolados e de Recente Contato (OPI), Centro de Trabalho Indigenista (CTI), and Comissão Pró Índio do Acre (CPI-Acre), Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS), Rainforest Foundation Norway (RFN), World Resources Institute

Sources:

- Centro de Trabalho Indigenista, Corredor Territorial Yavarí-Tapiche, 13 August, 2024. ↩︎

- Centro de Trabalho Indigenista, Corredor Territorial Yavarí-Tapiche, 13 August, 2024. ↩︎

- Centro de Trabalho Indigenista, Corredor Territorial Yavarí-Tapiche, 13 August, 2024. ↩︎