Members of indigenous-led forest patrolling organization Geoindígena in Panama’s Darien region. IMAGE CREDIT: Tristan Martin

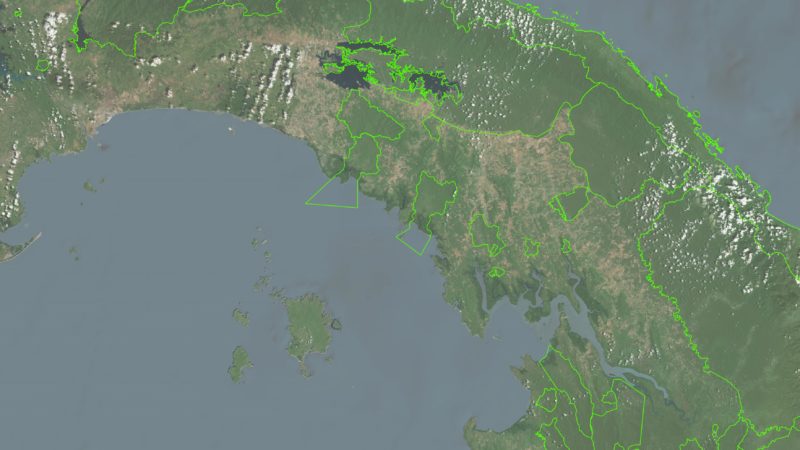

- The Darien Bioregion of Eastern Panama is being deforested at an alarming rate, driven in part by illegal trafficking running widespread through the region.

- Local media and policymakers often blame indigenous peoples for the trafficking, which disproportionately happens on indigenous peoples’ forested land—even though indigenous peoples are more likely to be victimized by the illegal traffickers moving through their land, rather than profit from participation.

- Rainforest Foundation US’s partner Geoindígena is actively fighting to stop rainforest destruction in the region, thereby strengthening relationships with federal environmental protection efforts and bolstering indigenous peoples’ case for land claims in the eyes of those agencies.

“The Forests of Darien are in Danger Because of Illegal Logging,” declared a 2015 headline in La Prensa, Panama’s newspaper of record. Underneath that, a sub-headline claimed that, “Panamanians—among them indigenous people—are involved.”

The headline is undeniably true. The Darien, a bioregion in Eastern Panama that abuts the Colombian border, suffers rampant deforestation. In these 11,399 square miles (about 2.95 million hectares)—an area approximately the size of Belgium—more than 40% of the rainforest has disappeared in the last 30 years, according to an article in the academic journal World Development. About 90% of the forest loss can be attributed to illegal logging.

Read more about deforestation in Panama.

But the sub-headline that implies that indigenous people are driving deforestation is a gross mischaracterization—and it’s one that’s widely held and oft-repeated in local media and by those in power. For example, in 2018 the United Nations’ regional coordinator of Environmental Governance Andrea Brusco intimated that indigenous peoples didn’t care about protecting their rainforest while speaking with a reporter. Brusco said that Panamanians living on untitled land—that is to say, indigenous peoples—would be more motivated to protect their forests if they had titles to the forests they lived amongst. While the intention may have been to advocate for indigenous peoples’ land titling, the message was that indigenous peoples in Eastern Panama were, at best, passively complicit in the deforestation.

But in reality, they’ve been suffering for it. Indigenous peoples’ lands are among the only forested lands remaining in the Darien. Their forest cover—which is even more vast than the region’s protected areas—make these territories ideal routes for traffickers who want to keep their operations invisible from the air.

Rampant Criminality in the Darien

The Darien is perhaps most famous for the thing it lacks. Home to the “Darien Gap,” this is where the Pan-American Highway ends, where for 65 miles (106 kilometers) an otherwise unbroken stretch of road between northern Alaska and southern Argentina disappears.

Where roads disappear, so too does police oversight, which has resulted in the Darien becoming a focal point for transnational illicit trafficking. Cocaine moves from south to north. Firearms move from north to south. And countless other criminal enterprises are illegally trafficked here: from wildlife to logging to—perhaps most tragically—humans themselves.

This land is disproportionately held by indigenous peoples, such as the Emberá and the Wounaan, whose shared comarca (i.e. collective territory) is in the Darien. At 1,696 square miles (about 440,000 hectares), the comarca constitutes nearly 15% of the bioregion. An additional 22% of the bioregion is untitled indigenous peoples’ land.

And as illicit materials move through the Darien, indigenous peoples are blamed.

That can make it hard for untitled indigenous communities, like the Wounaan of Aruza, to secure legal recognition to the 2,532 square miles (655,785 hectares) of indigenous peoples’ territory that remains untitled and thus up-for-grabs in the eyes of the Panamanian government.

“The public sentiment has an impact on titling,” says Cameron Ellis, Senior Geographer for Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS). “A lot of people in Panama say: Indigenous peoples already have plenty of land, and what are they doing with it? They’re smuggling drugs and cutting down trees.”

But the truth, Ellis says, is that illicit trafficking hurts indigenous peoples the most. That’s because as violent criminal syndicates cut penetration routes through these forests to move their supplies, indigenous peoples are the ones who come face to face with the danger. The syndicates also coerce indigenous people into supporting their operations with a “plata o plomo” diplomacy—silver or lead. In other words: get paid by the syndicates, or get brutalized by them.

Forest patrollers working with RFUS have been held against their will for hours by narcotraffickers, says Ellis. The message is clear: this part of the forest is no longer safe. With hunting, fishing, and farming grounds thereby sometimes cut off, food scarcity follows.

Geoindígena As Proof of Indigenous People as Forest Protectors

There’s mounting evidence that indigenous peoples are the best protectors of rainforests in the world, regularly outperforming forest protection entities like national parks. And scientists have found that the Darien’s rainforests capture an unusually high amount of carbon, a key component to neutralizing the effects of greenhouse gas emissions in the fight against climate change. But it’s one thing for this evidence to appear in scientific studies, and another for it to be accepted as an ironclad truth by the policymakers and government officials with the power to determine land titles.

In Panama (and throughout the world), there’s a long history of policymakers denying indigenous peoples territorial rights—and sometimes even expelling them from their lands—under the auspices of forest conservation.

That’s why an organization like RFUS partner Geoindígena is so important in changing the tone in Panama.

Using a forest patrolling (or “community monitoring”) program that’s technologically identical to RFUS’s Rainforest Alert, Geoindígena is an indigenous peoples-led technical services organization that supports indigenous land rights across the isthmus. Included in that support is the use of satellites and smartphones to detect and document illegal deforestation on their lands. Launched in 2018, Geoindígena was originally supported by RFUS, but since 2021 it has established autonomous lines of financing.

Learn more about how rainforest monitoring works.

Geoindígena’s work in the field is vital, not just for detecting deforestation, but for establishing constructive relationships with Panama’s Ministry of the Environment (MiAmbiente) and the National Land Authority (ANATI). Because Geoindígena works in partnership with both indigenous territories and government environmental agencies to stop deforestation, they have the potential to change ill-conceived notions about the role that indigenous peoples play in forest defense.

“Geoindígena has moved the needle in Panama,” says Ellis. “MiAmbiente having a relationship with Geoindigena profoundly changes things for land titling and territorial defense.”

Earlier in the year, MiAmbiente halted logging permits in forests near the village of Aruza. Says Ellis, “I don’t think they would’ve stopped it without Geoindígena and other allies stepping in.”

That help is integral.