44.2 million acres of Brazil’s Amazon rainforest burned in 2024. The area lost to fire in the Amazon grew by at least 66% compared to 2023, according to the MapBiomas organization’s Fire Monitor. September was the most devastating month with, with 13.7 million acres of forest burned—an area comparable to the size of Costa Rica—according to MapBiomas.

The number of fire outbreaks in the Brazilian Amazon surged by 42.3% compared to 2023. Data from INPE—Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research— revealed a total of 140,346 fire outbreaks in 2024, up from 98,639 in 2023. The all-time record was set in 2004, with 218,637 outbreaks.

The Brazilian Amazon already experienced a significant increase in fires in 2023, with at least 26.4 million acres burned, marking a 35.4% rise from 2022.

Other Amazonian countries, including Bolivia, also experienced a record number of fires in 2024. According to data from INPE, the country registered 90,026 fire outbreaks, the highest number since data collection began in 1998. Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Guyana also saw a huge surge in fires in 2024.

Tropical forests such as the Amazon are very humid, and under natural conditions they rarely burn—unlike many forests in the western United States where fire is a natural part of the forest’s life cycle.

In the last few decades, two interrelated phenomena have driven Amazon fires: drought, and the expansion of industrial agriculture.

Forests cleared for cattle ranching, agriculture, logging, or illegal mining are cut and then deliberately set on fire once the felled trees are dry enough to burn. Typically, the surrounding forest is wet enough to stop the fires at the edges of new fields and pastures. But prolonged drought in the Amazon—linked to climate change and deforestation—means fires are escaping into neighboring primary forests and burning out of control across thousands of acres.

As more forests are cleared, new roads are built, and new fields are cleared for cattle and agriculture, a vicious cycle is created that both intensifies the drought and exposes more forests to fire threats and forest degradation.

Scientists warn this cycle is leading the entire Amazon basin towards a ‘tipping point,’ believed to occur when the combined effects of deforestation and degradation surpass a threshold of 20% to 25%. A study warns that the Amazon rainforest could reach this ‘tipping point’ by as soon as 2050. At that point, the world’s largest tropical forest would become so fragmented that it would no longer retain sufficient moisture to sustain itself, leading to catastrophic consequences for the global climate and life on Earth

Several factors have contributed to the massive increase in fires in the Amazon. The region is experiencing drier conditions, a phenomenon closely linked to climate change and intensified by El Niño. In fact, 2024 is the hottest year ever recorded on Earth. By June 2024, our planet had experienced 13 consecutive months of record-breaking temperatures, increasing the forest’s vulnerability to fires.

This year the region also experienced a historic drought for the second year in a row, fueling fires that spread through native vegetation. Low water levels in the region’s rivers made it difficult to combat the fires, leaving Indigenous and riverside villages inaccessible.

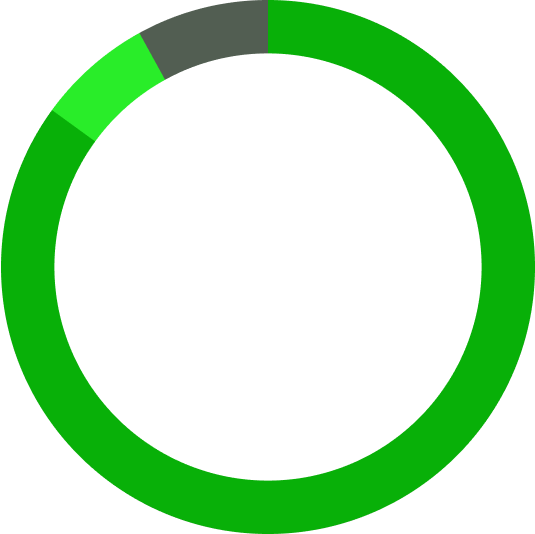

Area Burned in Brazil’s Amazon Annually Since 2019

Healthy communities can manage and protect their lands better than anyone. And healthy rainforests don’t burn.

Building on 35 years of steady, dedicated work with Indigenous partners in the Amazon and Central America, Rainforest Foundation US provides the tools, training, and resources to directly support in legal defense, land titling, and monitoring. We also partner and collaborate with Indigenous peoples and local communities to strengthen their organizations. This enables them—the best defenders of their rainforests—to continue to manage their lands with the knowledge and care they have sustained for thousands of years.

Indigenous peoples are the most effective forest stewards. Rainforests held by Indigenous peoples have fewer fires and lower fire temperatures, meaning they’re better able to resist forest loss. Data also shows that rainforests managed by Indigenous peoples contain greater carbon density than state-managed forests and foster higher levels of biodiversity. In other words, these forests are vital to our planet and play a crucial role in combating the climate crisis.

One of the best ways to protect the Amazon from destruction from fire, mining, industrial ranching, and illegal-logging is to secure and expand the land rights of Indigenous peoples living in these territories. Ensuring Indigenous peoples and local communities have rightful governance and control over their territories, as well as access to the necessary technology, training, and resources to manage and protect their territories is crucial to preventing fires and protecting the region’s biodiversity and cultural heritage.

The satellite map below displays real-time fires and Indigenous peoples’ lands. The majority of fires are observed outside Indigenous territories, typically ceasing at their boundaries.

“We know that reducing deforestation and supporting Indigenous and local communities’ fire brigades is effective in both preventing and mitigating the impact of fires. However, with the Amazon in an extended drought and quickly approaching a tipping point, the scale of these fires presents a very new type of threat to the region. Protecting forests and traditional fire management practices will need to be reinforced with more systematic state measures, including accountability, emergency response planning, and aerial fire suppression,” suggests Cameron Ellis, Field Science Director of RFUS

The response to fires must be coordinated among various government agencies and institutions, with increasingly sophisticated accountability methods and increased fines.

“The mixture of climate change with El Niño contributes to highly flammable soil conditions, but the Amazon is not a biome that naturally burns. The response to fires in the Amazon should be a command-and-control strategy, with joint operations and rigorous penalties,” adds Christine Halvorson, Program Director of RFUS.

Immediate actions are needed to protect this vital biome and its communities. And raising awareness about the severity of the situation and the need for immediate action to protect the Amazon is critical to ensuring a more sustainable future for the Amazon rainforest and its inhabitants.

Take Action NOW on rainforest protection and Indigenous peoples’ rights

Are you interested in other ways to support us?

Learn more here.

Get news, updates, and stories from the rainforest—straight to your inbox.

Land Acknowledgement

Rainforest Foundation US recognizes and honors the original peoples of the land on which our headquarters is based in Brooklyn, New York: The Ramapough Munsee Lenape, who have cared for these lands and waters for generations. We ask the Ramapough Munsee Lenape people’s permission to be here as their guests and ask their blessing for the good continuation of our work.

How much do you know about the world’s rainforests?

In honor of World Rainforest Day, we’ve put together a quiz to test your knowledge about these vital ecosystems. See how much you really know—and learn a few facts along the way.