On the heels of a recent survey of indigenous communities in Peru revealing widespread unfamiliarity with COVID-19 and widespread hesitancy about the vaccine, Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) has teamed up with representative indigenous partner organizations on a multilingual COVID-19 awareness campaign.

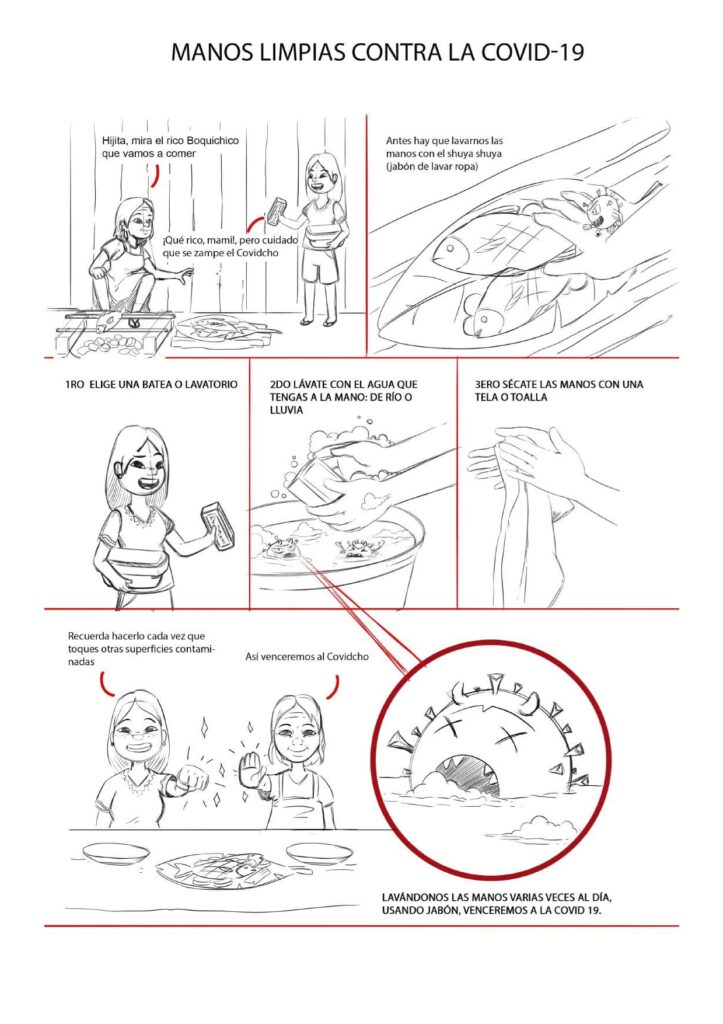

The campaign, which will be run in eight indigenous languages as well as Spanish, will consist of broadcasts, podcasts, and infographic comics, and will be distributed throughout 123 rainforest-dense departments of Loreto and Ucayali.

The campaign is the latest iteration of RFUS’s COVID relief effort in Peru, which began in early 2020, and was launched with the help of the Center for Information and Education about the Prevention of Drug Abuse (CEDRO) and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

If our recent survey results are an indicator, the campaign is sorely needed.

Conducted last month in 40 indigenous communities in the aforementioned departments, the survey shows how unaware of COVID-19 many in these communities remain. In the starkest of terms: A large majority of the indigenous people we surveyed can’t identify the virus’s symptoms, don’t know how to curb its spread, and don’t trust the vaccine.

The lack of information isn’t due to indigenous obstinance, but rather to a failure of the Peruvian government’s public information priorities, says Katya Zevallos of the Indigenous People’s Organization of the Eastern Amazon (ORPIO), one of our partner organizations on the campaign.

“The government of Peru has spent a lot of money to provide people with information about COVID-19. But only one sector of the population: the ones that have internet, smartphones, cell phone service,” Zevallos says.

Too often, indigenous communities have been left in the dark. And looking at Peru’s pandemic numbers, that informational failure could lead to disaster imminently.

How Peru’s Amazonian Communities Are Responding to COVID-19

Because of the lack of information, there’s a lack of basic COVID safety measures amongst indigenous peoples that over the last year have become commonplace elsewhere. Of our survey respondents, 67.5% didn’t know that the virus spreads more easily indoors. More than half (54.3%) share food and drink receptacles when meeting friends outside the household. More than half (50.4%) don’t wear masks outside the household. Recognition of COVID symptoms is likewise perilously low, e.g. only 9.3% and 4.1% of respondents knew that those infected with COVID-19 might lose their sense of taste and sense of smell, respectively.

Meanwhile, the pandemic in Peru has worsened. Fueled by the P.1 variant first discovered in Brazil, a deadly second wave has kept case numbers high, while vaccine distribution crawls. As of press time, Peru’s fully vaccinated population was only 2.2%—magnitudes behind the United States and Europe. For Peru’s indigenous Amazon population—many of whom are far removed from the health care available in cities—the potential for catastrophe is undeniable.

The Ministry of Health recently announced plans to send tens of thousands of AstraZeneca doses to indigenous Amazonian communities. But our survey suggests that vaccine hesitancy could blunt the effectiveness of that aide. Of the community members surveyed, 66.2% said they did not want to receive the vaccine.

Gregorio Mirabal, Coordinator of the Congress of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon River Basin (COICA), an umbrella organization of indigenous rights in the Amazon Basin, spoke impassionedly about the lack of governmental outreach at a press conference last Tuesday on the survey results.

“We’re asking for a plan about prevention and vaccination,” Mirabal said.“Where is the plan? Where’s the dialogue? Where’s the differentiated approach to indigenous communities?”

One silver lining in the survey was that much of the respondents’ vaccine resistance is “soft”: that is to say, of the 66.2% who didn’t want the vaccine, only 32% indicated that their mind was made up. Our hope is that this campaign will raise safety measures and bring vaccine hesitancy down, protecting communities from more serious outbreaks.

How the COVID Information Campaign Will Work

Our campaign for greater COVID-19 awareness will be done in partnership with the indigenous-led organizations ORPIO and the Regional Organization of AIDESEP in Ucayali (ORAU). Slated to roll out in early June, it’ll feature a series of radio spots, podcasts, and twelve comic-style infographics. The graphics will be blown up onto banners for display in public spaces, and compiled into a calendar: one infographic per month.

The calendars are an attempt to meet indigenous communities where their interests are, explains RFUS’s Country Director for Peru, Tom Bewick, who adds that “In most indigenous houses, there’s not that much on the wall—but you almost always see that calendar.”

The messages contained therein will be likewise directly reflective of survey results. In one infographic, readers will be dissuaded from self-medicating. With Peru’s healthcare system cumbersome, expensive, and oftentimes inaccessibly far away from indigenous communities, some indigenous peoples are tempted by unproven over-the-counter solutions that friends and neighbors have utilized. As has happened elsewhere in the world, scientifically unsound solutions spread rampantly, word-of-mouth, boosted by the mirage of proof that comes from the high variability in COVID-19’s course-of-illness: I took it and I got better, so you should take it too.

The entire campaign aspires to hone in on both indigenous preferences and their knowledge gaps while dispensing public health information. To better do that, we’re also working with indigenous health promoters and other indigenous leaders, who will serve as valuable interlocutors to communities historically wary of outsiders.

In addition to Spanish, the campaign messaging is being translated into Kichwa, Ticuna, Yagua, Shipibo-conibo, Ashaninka, Bora bora, Muri-muinani, and Maijuna. When asked about the need for translating into indigenous languages, given the widespread use of Spanish throughout the nation, Zevallos says it speaks more to the difficulty of the virus than the difficulty of Spanish.

“[Many indigenous people] understand Spanish, but not fluently. Not with difficult concepts. Not with something that nobody in the world understands anyway: something like COVID-19.”