- The Wapichan Headwaters are the ancestral lands of Guyana’s Wapichan, Macushi and Wai Wai peoples. A haven for biodiversity, they form the vital watershed that feeds the region’s major rivers.

- Much of the area is currently under threat from unregulated gold mining and deforestation.

- To protect the Headwaters, the South Rupununi District Council, with support from Rainforest Foundation US, has developed a management plan rooted in Indigenous stewardship.

“If we can’t protect the Headwaters now, future generations won’t see freshwater like we do,” said Uriel Mandukin from the Katoonarib Village, speaking at a meeting on the urgent need to safeguard the Wapichan Headwaters.

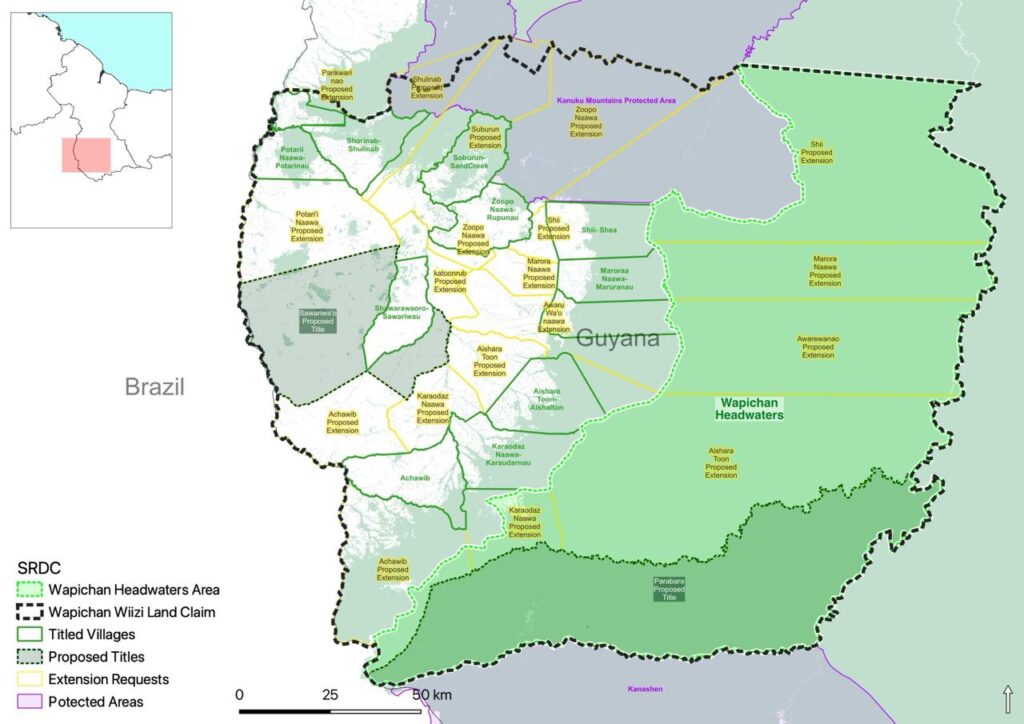

Spanning millions of acres in southern Guyana, near the border with Brazil, the Headwaters stretch across the eastern edge of Wapichan territory, also known as Wapichan wiizi, and are the ancestral lands of the Wapichan, Macushi, and Wai Wai Indigenous peoples. This mosaic of wetlands, savannahs, and mountains, all interwoven with dense forests, is home to nearly 6,000 known species, including 70% of all vertebrates recorded in Guyana. Animals rare and endangered elsewhere, like jaguars, giant river otters, and crested eagles, remain abundant here. The Headwaters also give rise to several of Guyana’s most important rivers: the Rupununi, the Rewa, and key tributaries of the Essequibo, the country’s main waterway and lifeline for the capital, Georgetown. As part of the Guiana Shield, this ecosystem plays a critical role in regulating rainfall and temperature patterns across the Amazon basin and beyond, underscoring its importance for regional and global climate stability.

A Living Connection Between Land, Water, and Identity

For the Wapichan peoples of Guyana, these lands carry the memories of their ancestors and are an archive of their identities as Indigenous peoples. Sacred caves are ancient burial grounds, while ancient rock carvings and paintings, representing stories and knowledge, date back thousands of years. These sacred sites carry immense spiritual weight and are irreplaceable.

The rivers that originate here provide food and water, and are central to spiritual ceremonies. Many of the fishing grounds are shared with neighboring communities, strengthening bonds that span entire watersheds. Beyond the waterways, the land is rich in plants and trees essential to construction, traditional crafts, and herbal medicines, making the forest both a pantry and a pharmacy for those who call it home.

Mounting Threats

The Wapichan Headwaters extends over nearly 3.5 million acres (1.5 million hectares), roughly the size of the state of Connecticut. While some areas of the territory are formally titled Indigenous lands, the Wapichan and Wai Wai have taken steps to secure legal recognition for the entire Headwaters, filing one land title request and six title extension requests that are currently advancing through the government process.

In certain areas, such as Marudi Mountain, an application to extend Indigenous land boundaries overlaps with an existing mining concession. Miners have also expanded operations beyond licensed areas, encroaching further into these territories. The result is a complex web of overlapping claims, unrecognized territories, and competing interests between resource extraction and Indigenous rights. Unregulated gold mining has not only scarred the landscape but also triggered a surge in malaria cases, disproportionately impacting Indigenous communities and pushing the region into a dual environmental and public health emergency. Meanwhile, the majority of the Headwaters remains untitled and unrecognized by the Guyanese government, leaving these lands vulnerable to further environmental degradation.

Compounding these challenges are the escalating impacts of climate change. As rainfall becomes more erratic and dry seasons grow longer, food production has become increasingly unstable. “Since last year, we’ve been facing water scarcity in Aishalton, and climate change is making everything worse,” said Immaculata Casemiro, coordinator of the Wapichan Women’s Movement. “Water for us is everything, clean and healthy water. Without it, who are we as peoples?”

Communities can also no longer rely on traditional planting calendars and are being forced to adapt. Fires, intensified by prolonged drought, now pose growing threats to wildlife, human health, and homes. The Wapichan’s seasonal fire calendars, once essential tools for maintaining ecological balance, must now be reimagined to reflect shifting climate patterns.

A Roadmap for Protecting the Headwaters

To protect the ecological and cultural integrity of the Wapichan Headwaters, the South Rupununi District Council (SRDC), with support from Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS), developed the Wapichan Headwaters Management Plan. Developed through two years of community meetings across the South Rupununi, this community-led roadmap outlines how communities will continue stewarding the land and its resources into the future. The plan reflects strategies for maintaining the deep connections between the Wapichan and their ancestral lands, connections that have existed for millennia, in the face of growing threats.

I’ve been talking about the protection of the Headwaters for a long time…I see the headwaters as important, especially for women, because we care about the future and the world we leave behind for future generations.

– Immaculata Casemiro, coordinator of the Wapichan Women’s Movement

The plan prioritizes six key actions: gaining legal land recognition, influencing national policy on waterways and land use, securing conservation designation, implementing local regulations for farming, fishing, hunting, gathering, and mining, expanding youth education and communications, and developing alternative livelihoods. Importantly, most of these actions can move forward even without official land titles—though the Wapichan are clear that they would oppose any conservation designation that fails to recognize their rights to the land.

When it comes to formal land titling, government processes can be slow and often require ongoing vigilance and advocacy from Indigenous organizations. Yet once land titles are granted, the management plan provides a clear roadmap for communities to continue stewarding these territories efficiently, collaboratively, and sustainably for the long term, as they have always done. At the heart of the Wapichan’s approach is the conviction that no one knows or protects this land better than its original stewards.

Why Indigenous Stewardship Works

New research confirms what Indigenous communities have long known. Lands managed by them experience significantly less deforestation, especially when communities hold full legal title to their territories. Titled Indigenous territories are also crucial for protecting public health in forest regions, with the greatest benefits found near communities with secure land rights.1 In the Headwaters, where illegal and unregulated gold mining is driving a surge in malaria, recognizing and formally titling Indigenous lands is both a public health and environmental imperative.

Under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, Guyana has pledged to conserve 30% of its lands and waters by 2030, yet with only 8.5% currently protected, supporting Indigenous-led land management and granting land titles will be essential. The Framework makes clear that conservation targets must not come at the expense of Indigenous rights, and governments are obligated to respect and recognize Indigenous land tenure when establishing new protected areas. If recognized by the government of Guyana and implemented through formal land titles, the Wapichan Headwaters plan would do exactly that, bringing together climate action, justice, and the ancestral knowledge of those who have cared for these forests for generations.

The Path Forward

The Wapichan Headwaters Management Plan represents a critical opportunity for Guyana to protect biodiversity, safeguard freshwater systems, and strengthen climate resilience, all by recognizing and respecting Indigenous rights and leadership. It’s a win-win: when Indigenous territories are legally recognized, communities can continue doing what they have always done, protecting these lands for future generations while contributing to the global fight against the climate crisis.

– Laura Piccoli, Program Manager, Rainforest Foundation US

Looking ahead, it remains to be seen whether the Guyanese government will embrace the Wapichan Headwaters Management Plan as a global model for rights-based environmental protection. To bring it to life, the government must act: accelerate land titling, retire inactive mining claims, and support meaningful dialogue with Indigenous communities to explore protection models grounded in their values. Crucially, Indigenous peoples must have a seat at the table in shaping national policies. Until these steps are taken, the Headwaters, and the communities that depend on them, will remain vulnerable.

Protecting the Wapichan Headwaters matters not only to the Wapichan, Macushi and Wai Wai peoples but to the health of the entire Amazon, which relies on the forests of the Guiana Shield to maintain temperature and humidity patterns across the basin. Defending these lands is also defending a way of life. As Kid James, Coordinator at SRDC, put it, “One of the things we take for granted is how we use water here. Sometimes you don’t realize how important what you have is, until you don’t have it anymore. And that goes for land, too.”

Learn more about Indigenous-led rainforest protection and keep up with the latest developments in our work by signing up for our email list today.

Sources:

- Inside Climate News, Deforestation Threatens Public Health. Securing Indigenous Land Rights Can Help, Researchers Find, September 11, 2025. ↩︎