Photo Credit: Rainforest Foundation US

When Fernando Durán moved to Buen Jardín de Callaru 5 years ago, he struggled initially to find a stable livelihood. He was able to team up with his brother, who lived in Buen Jardín, to farm cacao and worked small jobs here and there that helped him earn enough income to support his wife and son. But the going was tough, especially since basic tools like shovels and machetes were in short supply in this impoverished, isolated Ticuna community.

At the time that Fernando arrived, the village of Buen Jardín de Callaru had no formal source of income and no established economy. Inhabitants relied strictly on hunting; fishing; small-scale cacao, cassava and fruit cultivation; as well as gathering other foods from the bounty of the surrounding forest. This way of life was nothing new to the indigenous Ticuna people, who have subsisted on the wealth of the region’s forests for generations. But since re-settling here on the Callaru River in the 19th century after rubber tappers pushed them out of their original territory, the community was experiencing an increase in illegal invaders that burned their forests, plundered their natural resources, and threatened community members.

The community of Buen Jardín de Callaru secured their collective land title in 2001, which, on paper at least, legally protected their rights to this land. However, the title did not prevent illicit coca producers from trespassing and setting fire to vast areas of rainforest. Nor did it prevent illegal loggers from looting the territory of all of its valuable timber. When the community tried to confront them, they responded with intimidation and violence, paralyzing the community. The area was never visited by the state’s environmental enforcement agents who are charged with managing illegal incursions like these. Tensions were high between the community and the criminal networks that operated with total impunity.

Monitoring With Technology for a Secure Forest

In 2017, Fernando was invited to take part in a training on territorial monitoring in Iquitos ran by the regional indigenous peoples’ organization, the Organization of the Indigneous People of the Eastern Amazon (Organización Regional de los Pueblos Indígenas del Oriente, or ORPIO) and the local Federation of the Ticuna and Yaguas Communities of the Lower Amazon (Federación de Comunidades Ticunas y Yaguas del Bajo Amazonas, or FECOTYBA), supported by Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS).

“That training opened our minds and made us see beyond what was there,” recalls Fernando, referring to the prospect of combining community action, new technologies like drones, and rigorous documentation to address the illegal deforestation taking place in their territories.

While the project excited Fernando and his fellow community members, they were initially skeptical that this program could produce results for the community. Far too often, government agents would arrive in Buen Jardín de Callaru and make promises that never amounted to anything. “The people here were so tired of the lies that kept coming here,” he recalled. No one expected the program to actually get off the ground.

Forest Monitoring: Success Breeds Success

Before long, a contingent of community-based territorial monitors had taken up the new technology and regularly patrolled the boundaries of their communal territory to track weekly deforestation alerts that came in on their smartphones.

After the community engaged Peruvian authorities to investigate a collective complaint of illegal deforestation in December 2018, the community was struck by how illegal incursions declined significantly.

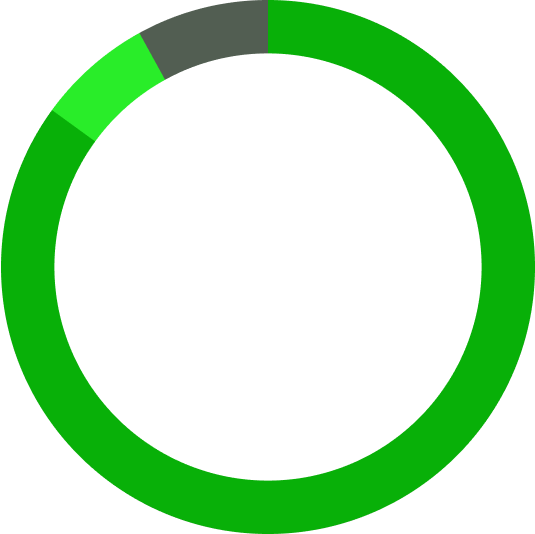

Over the following year they measured that deforestation on their territory decreased from 12% in 2018 to 0% in 2019–a trend that continues into 2020. Indeed, many communities implementing the same monitoring program saw similar outcomes, which were reported on in a study that provided preliminary results on the effectiveness of a community-based monitoring strategy on deforestation levels across the region.

From Forest Defense to Forest Restoration

With deforestation halted by the monitoring program the community began thinking about new possibilities. The newfound security of their territories generated hope for a brighter future. In the many community meetings, Fernando joined others in emphasizing the need to strengthen their local economy.

But initially, only a handful of community members assembled to take part in these discussions. Suspicions around the project persisted, however, keeping many from taking part. Though Fernando had felt the need to decline an earlier opportunity to join the monitoring team to focus on his growing farming operation, he continued to contribute to meetings. He knew that it was important for their allies to know the true needs of the community. The benefits from prior initiatives were rarely felt by the community at large due to poor coordination and information-sharing at the community level.

“I really wanted to see improvements in the community that embraced me years ago and felt that I could do something,” he said.

Sometimes he felt judged by members of the community for the successes that he had achieved from his farming operation, which he lamented required long and hard hours of physical labor. But over time, he felt like he was able to gain the community’s confidence.

A Reforestation Committee was established and charged with making decisions on what to plant, in what areas, how to monitor the seedlings, and maintain shared accountability. Soon enough, Fernando was elected to serve as president of the Committee. He was humbled, knowing that his colleagues trusted him to lead the effort in a good way.

Watch the full video recounting the reforestation project of Buen Jardín de Callaru

The community members agreed that replanting deforested areas with previously logged hardwoods and income-generating fruit species would be ideal. The species and reforestation areas were determined collectively by the community members, and then ORPIO and RFUS helped procure the seedlings, tools and technical training.

“By reforesting in this way we benefit two-fold,” explained Fernando. “First, in having fruit trees and the fruits that those are going to produce that we can sell for income… and secondly that the hardwood varieties will continue to develop and grow until the fruit tree has reached an age where it is no longer able to produce, leaving us the timber.”

The committee also determined that the place to start reforesting should rest with those in the community who were deemed to need the most support. In this case, they would begin with two plots of land appointed to Robinson Edwin Cobache and Jamber Pisco, both of whom had families to support and little chances to enter the markets on their own.

ANCESTRAL SYSTEMS OF COLLECTIVE ACTION TAKE ROOT

Over time, Fernando was impressed by the way in which the community united around a sense of common purpose, revitalizing a system of collective work used since Inca times called the “minga.” The minga in Buen Jardín de Callaru saw families, community members and even members of neighboring communities coming together in solidarity to make the dream of replanting their forest a reality.

“We started from scratch,” Fernando recalls. “We started as if there had been nothing.” Then one day some thirty-odd community members joined in on the construction of the seedling nursery. Weeks later, members of two neighboring communities joined the minga, bringing seedlings of plants that were not easily attainable around Buen Jardín de Callaru. When the day came to plant the seedlings, “children, men and women were all preparing the soil and planting, finishing rapidly as a team.”

“The most incredible thing was that people were suspicious,” said Fernando. “But what I admire most is how they came together. Most people here are not united, so I had my doubts… I didn’t think that they would unite for a common purpose, but then it happened.”

MINGA: A MODEL FOR CLIMATE ACTION?

As news of the successful monitoring and reforestation work of Buen Jardín de Callaru spread, surrounding communities began to express interest in the monitoring-to-reforestation model. As a result, in August 2020, Francisco Hernandez Cayetano, President of FECOTYBA, with the support of Rainforest Foundation US, facilitated agreements with two additional communities in the region—Bufeo Cocha and Santa Rita de Mochila—to transfer knowledge and capacities to expand the program’s footprint.

When community members of Puerto Alegre, San Juan de Barranco and Paraíso joined the minga of Buen Jardín the Callaru, Fernando cited that they brought native plants and hardwoods so that the community could reforest what they no longer had, to reforest what had been deforested. His dream is for this project to grow and contribute to mingas in other communities. “Then our seedling nursery can supply them as they enter this project. So we would already be the providers of seedlings for them.”

Imagine for a moment the future if our global society could embrace the concept of the minga the way Buen Jardín de Callaru and its neighbors have. Could we unite like they did, to address the climate emergency upon us? Could we join hands in solidarity, bringing our relative strengths to the table to help those less fortunate? Could we build on sustainable models of development that grow the economy while nurturing environmental and human health? The answer is that it is possible, that it is in our best nature, and that we must.