A bulldozer rests in the middle of the village of Rio Hondo after cutting a road in from the Pan-American Highway.

Initial reports from Rainforest Foundation US’s partners on the ground in Panama indicate that miners, loggers and traffickers are exploiting the global shutdown to increase activity, and expand into new territories. As the pandemic closes down businesses, including many routine government functions, and attention is drawn elsewhere, there is a real risk that unscrupulous actors will take advantage of the crisis to occupy new lands and expropriate the valuable natural resources that indigenous peoples in the region depend on.

A lesson from the Darien

Amidst the uncertainty and anxiety of COVID-19, this experience offers a reminder of how epidemics have shaped cultures and landscapes over time.

History shows that disease and epidemics have had a major impact on the indigenous peoples of the Americas and by proxy the rainforests they managed. By some accounts, measles and smallpox wiped out up to nine tenths of many indigenous populations—often reaching communities years ahead of the first Europeans to step foot on their lands—leveling immense civilizations, leaving the world with the mistaken impression of barren continents.

In the easternmost province of Panama bordering Colombia, the Darien is currently home to dozens of indigenous communities rich in culture and in the biodiversity that surrounds them. The landscape contains one of the largest intact forests in Mesoamerica and, in a twist of fate, remains standing in large part out of concern for the spread of Foot and Mouth Disease from South America to Central and North America.

Foot and Mouth Disease is a viral infection that attacks hooved animals such as cattle, pigs, and goats causing a high fever and blisters on the feet and in the mouths of animals. Outbreaks have been recorded worldwide since the mid 20th century, causing entire populations of livestock to be eradicated to control the spread of the disease. Given the rapid evolution of the virus, vaccines are regularly updated to be effective against new strains as they emerge.

The only interruption in the 18,640-mile-long Pan-American Highway that extends from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego on the southern tip of the continent is 106 kilometers of rugged mountains and dense tropical forests separating Panama from Colombia, known as the Darien Gap. Roadless by design, these lands are the ancestral home of the Emberá, Guna and Wounaan peoples who have defended them against outside encroachment for generations.

Plans to construct a road connecting North and South America have abounded for centuries. One of the more formidable initiatives was launched by the United States government in the 1970s. The U.S. earmarked $100 million to complete the missing stretch of the Pan-American Highway. However, environmental, human rights and especially epidemiological concerns ultimately cut the project short. Panama at the time had no occurrence of Foot and Mouth Disease. Although thousands of cattle were vaccinated and quarantined against the disease on the Colombia side of the border, the virus was not contained to the degree that would have permitted the highway project to continue as planned. The effort was ultimately abandoned in 1975.

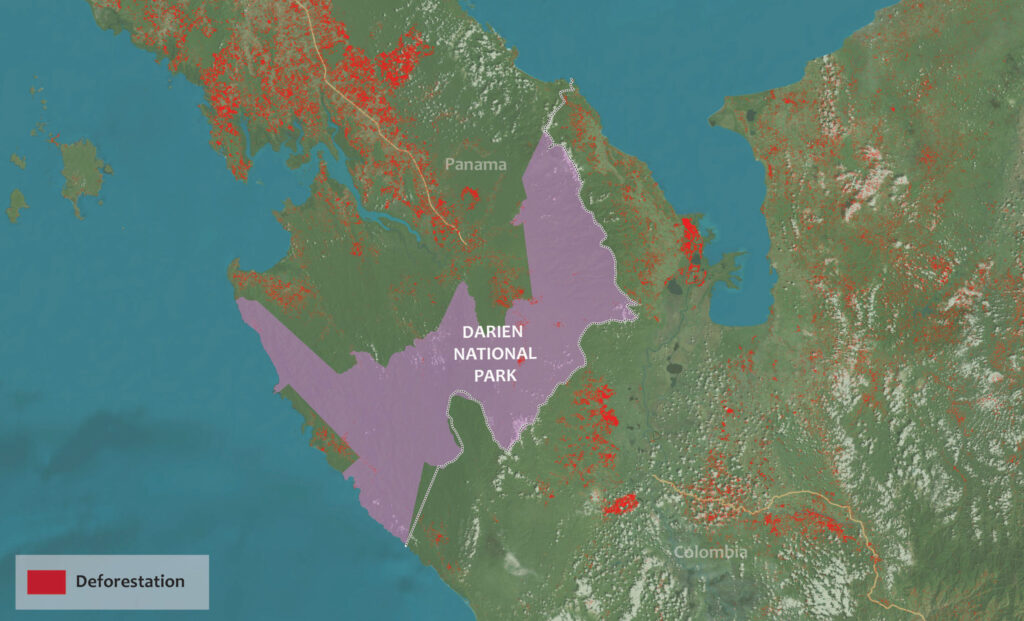

The Darien remains a signature case in how epidemiological concerns affected, and ultimately protected, a landscape and its peoples. By 1980 the Panamanian Government formally protected much of the region within the Darien National Park. Soon after, the UN declared the area a World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve.

The Darien under COVID-19

While the Darien is no longer an active target for highway development, the indigenous peoples and forests of the region are facing a growing list of threats that could be exacerbated by the introduction of the novel coronavirus.

The lack of roads has largely spared the region from many of the threats facing other Central American forests, such as clearings for cattle ranching and intensive agriculture. The dense forest canopy, however, lends cover to an illicit economy of drug trafficking, human trafficking, land trafficking, and land invasions that flows through the Darien.

Under normal circumstances these activities threaten the lives and forest-dependent livelihoods of the indigenous Wounaan, Emberá and Guna communities in the region. Indigenous leaders are threatened or extorted by criminals passing through their territories, and whole swaths of their land become inaccessible for farming or hunting because the risk of encountering armed groups is too high. Despite protections, deforestation in the area over the past decade has been rampant, in large measure still driven by the expansion of cattle ranching, commercial and small-scale farming and the legal and illegal trade in timber.

The short-term risks of intrusions into isolated indigenous territories includes the spread of COVID-19 to communities who have few natural immunities and some of the lowest level of access to health services of all Panamanian citizens. The loss of elders, being particularly vulnerable to this strain of virus, could mean the loss of volumes of ecological and cultural knowledge that keeps these communities vibrant and thriving.

Over the long term, intrusions could spur increased deforestation and fragmentation of the forest which leads to a decrease in ecological function. Furthermore, the social fabric of the communities could be threatened as additional rounds of deadly conflict erupt between indigenous peoples defending their territories and invading loggers, ranchers and colonists.

Indigenous peoples prepare against COVID

Rainforest Foundation US’s partners in Panama, including Wounaan, Embera and Guna civil society organizations and the National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama (COONAPIP), have been working with the government to translate COVID-19 prevention information into the seven indigenous languages spoken in the country and coordinate a safe way to deliver emergency supplies to communities that have been cut off from access to regional towns and cities. Some indigenous territories have cut roads or blocked rivers in an attempt to protect their communities from outsiders who could bring in the virus.

Rainforest Foundation US is looking for ways to mobilize further support to COONAPIP and others as new and urgent needs arise. Over the long term, strengthening territorial control based on clear and legally recognized land rights will ultimately be the best way to protect the cultural and biological diversity of the unyielding Darien Gap.

At this time COVID-19 may be the greatest risk to these lands, but if nature tells us one thing about the lessons learned from the Foot and Mouth Disease epidemic it is that respecting the “gaps” between us is sometimes the wisest way to keep people and landscapes healthy.