FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

July 12, 2021

For more information, or for interviews, kindly contact:

Wanda Bautista, [email protected]; WhatsApp/mobile: +1 302 233 5438

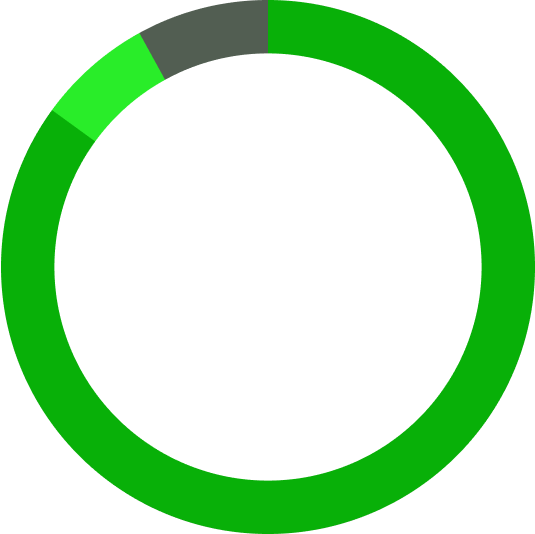

Communities saw a 52 percent reduction in forest loss in the study’s first year and a 21 percent drop in the second year.

New York, NY — (12 July 2021) A landmark study shows that indigenous peoples patrolling the Amazon for deforestation with smartphones and satellite data can be a powerful force in the battle against the climate crisis.

The randomized controlled trial carried out in the Peruvian Amazon assessed the effects of indigenous forest community monitors in reducing deforestation when equipped with satellite-based alerts.

The study found a 52% drop in deforestation the first year and 21% in the second year, compared with similar communities that did not adopt the approach. These reductions in forest loss were especially concentrated in communities facing the most immediate threats from illegal gold mining, logging, and the planting of illicit crops like the coca plants used to manufacture cocaine.

Researchers report these and other findings in a peer-reviewed study in the July 12th issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

This study represents one site in a larger study of community monitoring of natural resources conducted in communities across six countries – Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Liberia, Peru, and Uganda. A second study in PNAS synthesizes the findings across studies, revealing that territorial monitoring reduces natural resource overuse across the board.

The findings in the Peru study are the latest amidst a flurry of reports showing that recognizing indigenous peoples’ rights to their territory is the most effective way to preserve natural tropical landscapes.

Jacob Kopas, co-author of the study, says that “Should our results hold up elsewhere, they would suggest that similar community-based monitoring programs implemented by indigenous peoples across the Amazon can help contribute to sustainable forest management on a larger scale.”

Technology-based monitoring and enforcement by local communities and state officials could promote rainforest conservation in order to combat the climate crisis. More than one-third of the Amazon rainforest falls within the approximately 3,344 formally acknowledged indigenous peoples’ territories.

From 2000 to 2015, 17 percent of Amazon deforestation occurred in national protected areas or territories registered to indigenous peoples, while 83 percent occurred in parts of the Amazon that are neither under indigenous peoples’ control nor government protected.

Research indicates that the forests on indigenous peoples’ lands worldwide contain 37.7 billion tons of carbon, equivalent to 29 times of the annual emissions from all passenger vehicles in the world. Cutting down trees releases vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, where it absorbs and radiates heat, contributing significantly to the climate crisis.

“Although formal recognition of indigenous peoples’ land tenure is key to protecting their lands from deforestation, it is most effective when combined with active forest management and robust community and local governance,” says Suzanne Pelletier, Executive Director of Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS), the rainforest and rights protection organization that helped facilitate the study.

Jorge Perez Rubio, the president of the regional indigenous organization, Organización Regional de los Pueblos Indígenas del Oriente (ORPIO), where the study was carried out, says that “The study provides evidence that supporting our communities with the latest technology and training can help reduce deforestation in our territories.”

“We now have quantitative evidence showing that giving deforestation data directly to forest communities works,” says Jessica Webb, Senior Manager for Global Engagement with World Resource Institute’s Global Forest Watch, a free online forest monitoring system.

WRI worked closely with RFUS and ORPIO to design the community-based forest monitoring methodology, helping to plan the study, and analyze the resultant data.

WRI’s Global Forest Watch tools were vital to the model. When satellite images record changes in the forest cover, an algorithm developed by the University of Maryland’s GLAD (Global Land Analysis and Discovery) lab detects the changes and issues deforestation alerts. The alerts are widely available through the Global Forest Watch online platform and its Forest Watcher mobile app.

Before the model was deployed, deforestation alerts rarely filtered down to remote rainforest communities, which lack reliable access to the internet. Villagers were unaware that invaders were clearing community land and they were powerless to stop them.

“What good does this information do if it’s only seen by a bunch of academics and people in glass buildings?” says Tom Bewick, Peru country director for RFUS, who was a principal architect of the study methodology and implementation. “The whole point is to put the deforestation information into the hands of those most affected by its consequences and who can take action to stop it.”

In consultation with ORPIO, the principal investigators identified 76 villages in the northern district of Loreto to take part in the study. From this sample, 39 communities were randomly assigned to participate in the monitoring program. Three opted out before the study began. Each community that was assigned to the monitoring treatment identified and trained three representatives to conduct monthly monitoring patrols to verify reports of deforestation. Meanwhile, 37 communities were assigned as the control group and retained their existing forest management practices.

Over the course of the study, indigenous technology experts in a regional data hub regularly gathered reports of suspected deforestation, including satellite photos and GPS information. Once a month, couriers navigated the Amazon river and its tributaries to deliver USB drives with the information to the remote villages. Upon arrival in the village, the monitors downloaded this information onto specialized smartphone apps, which they then used to guide their patrols to the locations of the forest disturbances.

In cases where the monitors identified unauthorized deforestation — typically conducted by outsiders harvesting timber or clearing land for farming, gold mining, or coca cultivation — they presented the evidence to a general assembly of community members for consideration.

In each case, the community would collectively decide upon the course of action. If drug traffickers were involved, communities may have decided to present their evidence to law enforcement authorities. In less risky circumstances, community members could intervene directly by declaring their rights and driving offenders off their land.

“Over the next decade, if nothing changes, indigenous peoples in the Amazon Basin are projected to lose 4.4 million hectares of rainforest, mostly to outsiders who encroach on their territories to cut down trees,” says Cameron Ellis, senior geographer for Rainforest Foundation US.

The study suggests that community monitoring with remote-sensing deforestation alerts represent one promising intervention to protect these territories.

“But if the community-based forest monitoring methodology could be widely adopted and local governance strengthened, forest loss in the Amazon could be reduced by as much as 20 percent across all indigenous peoples’ lands. If the approach were targeted to regions with high deforestation rates, forest loss in those areas could be cut by more than half,” says Ellis.

Using its own conservative calculations, and based on comparable projected outcomes, Rainforest Foundation US estimates that community-based forest monitoring in Brazil could save 415,000 of the 2.2 million hectares of rainforest in indigenous peoples’ territories likely to be lost over the next decade. In Peru, 186,000 of 500,000 hectares of at-risk rainforests controlled by indigenous peoples could be saved.

Over the course of the two-year study, the treatment communities prevented the destruction of an estimated 456 hectares of rainforest, avoiding the release of over 234,000 tons of CO2 emissions at a cost of about $5/ton. Rainforest Foundation US implemented the study’s community monitoring program at a cost of about $1/acre per year.

“The community monitoring program spearheaded by ORPIO and Rainforest Foundation US in Peru has vast implications for the survival of indigenous-managed forests across the Amazon,” says Gregorio Mirabal, general coordinator of the Coordinator of Indigenous Organizations of the Amazon Basin (COICA), the umbrella of indigenous peoples’ representative organizations in the Amazon’s nine countries. “Our network is ready to partner with Rainforest Foundation US to apply this technology-enabled model to our community forest protection initiatives basin-wide.”

The methodology for preventing deforestation could be scaled up quickly and at nominal cost. Satellite data are widely and freely available from WRI’s Global Forest Watch and other sources.

Bewick added that the project in the Peruvian Amazon province of Loreto is just the start. “Loreto represents everywhere,” he says. “There’s a solution here, it’s cost effective, and it works. The findings make a strong case to increase investment to scale the model. It would be good for the future: not only for Peru, but for our planet.”

###

Rainforest Foundation US was founded 30 years ago to promote the rights of indigenous peoples living in the rainforest and to support them and other forest communities in their effort to protect and defend their territories. rainforestfoundation.org

World Resources Institute (WRI) is a global research organization that works with governments, businesses and civil society partners to develop practical solutions to today’s pressing environmental and human development challenges. WRI currently has over 1,400 staff working in 12 offices, spanning Asia, Africa, Europe, the United States and Latin America. It focuses on urgent challenges in seven core areas: Food, Forests, Water, the Ocean, Cities, Energy and Climate. More information at www.wri.org.

ORPIO is an indigenous organization that works in 15 river basins in the Peruvian Amazon, among them: Putumayo, Napo, Tigre, Corrientes, Marañón, Yaquerana, Bajo Amazonas, and Ucayali. Among its objectives is the protection of indigenous peoples’ territories, promoting human development, defending rights, and strengthening indigenous governance. It represents 15 indigenous peoples and 21 federations. https://www.orpio.org.pe/