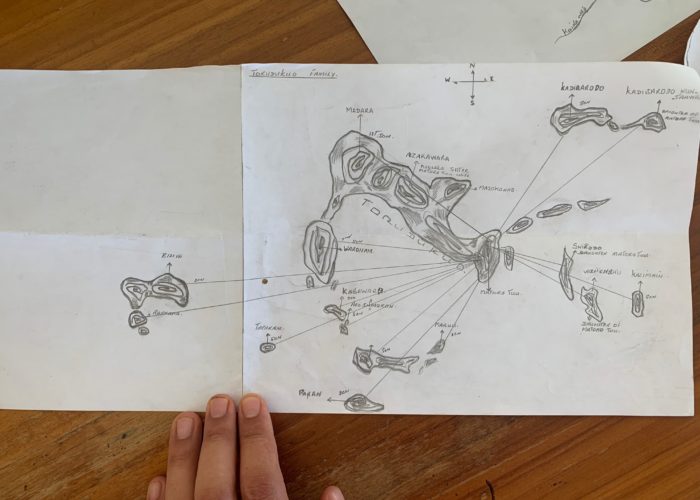

Members of Karisparu Village identify customary use areas on a map.

In the Patamona village of Chenapou, in Guyana’s mountainous deep interior, life’s sweetest moments are lived along the banks of the Potaro River.

“Every day, we’d go to the river and swim,” says Michael McGarrell, who grew up in the village. “We’d make slides out of the mud, and slide all day… sometimes you think you need modernity to enjoy life, but I was so happy. There was no television.”

Today McGarrell works as a Geographic Information Systems Specialist for the Amerinidian Peoples Association (APA), a non-governmental Indigenous Peoples organization in Guyana. But growing up, he and the other Patamona children of his village learned life skills at the water’s edge. As a small boy, McGarrell would plant wine bottles stuffed with cassava bread into the river floor during his swims, so that he could trap small fish like kiwik and wawa for a pepper stew that he’d boil over an open fire.

Sometimes, McGarrell would travel with his family by canoe down the Potaro to the Kaieteur Falls, a sacred place where the Patamona believe a great spirit resides.

The Potaro River was a place for fun, for food, for drinking water, and bathing water. For life.

Today, the Kaieteur Falls are one of Guyana’s most popular tourist destinations. Tourists scatter the ashes of their loved ones over the falls: a somber ceremony for the tourists, an act of desecration in the eyes of the Patamona. And elsewhere on Patamona land there are more material offenses: Mining operations have dumped mercury and other toxic pollutants into the river, killing fish and poisoning the drinking supply.

“That’s our source of food,” McGarrell says. “When you grant a mining concession at the source of our rivers, it puts our whole population at risk.”

Land Tenure Assessments are a Roadmap to a More Just Future

The indigenous peoples of Guyana regularly see miners, loggers, and other outsiders encroaching upon their land. Now, for the first time in Guyana’s history, there’s a nationally coordinated indigenous-led assessment of indigenous land holdings, spearheaded by the APA with support from the Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) and Forest Peoples Programme.

The evidence-based report was a massive undertaking, an 8-year research project on oft-contested territory that collectively covers around 6 million hectares: equivalent to the size of Croatia.

Some of the work was about coordinating myriad documentation. The team worked with 85 villages across Guyana, each with its own title and corresponding demarcation issues.

But it was also a matter of anthropological record-keeping, says Cameron Ellis, Senior Geographer at RFUS: gathering interviews from the field about sacred places and historical sites.

“When you’re trying to build a case for land rights that’s based on historic occupation of a landscape, establishing those sorts of stories is key,” Ellis explains.

Governmentally-Recognized Collective Titling as Primary Advocacy Goal

The most dramatic injustice in current indigenous land recognition of Guyana, the report finds, is the government’s nonrecognition of lands that are collectively held by multiple villages. These lands have traditionally been used for hunting and fishing, oftentimes in broad swaths of mountain or valley habitat, away from grassland villages.

Since British Colonialism, collective titling of indigenous lands has been excluded from recognition. Instead, land titles are recognized at the village level, to demarcate where indigenous people reside.

Laura George, Governance and Rights Coordinator for the APA, says that village-centered titling fundamentally misunderstands and misrepresents indigenous life in Guyana.

“Starting from colonialism, it was about taking away our lands. They declared that we were not intelligent enough to collectively occupy and develop our lands,” George says. “But as indigenous peoples, across villages, we collectively use the same resources.”

Mapping Errors Lead to Land Theft

Lack of collective titling isn’t the only shortcoming identified by the land tenure assessments. There’s also significant indigenous land loss attributable to poorly-drawn maps, where a village’s title describes different boundaries from those drawn on the governmental map by the Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission (GLSC). That’s because the multi-step process between titling and cartography is beset with problems.

“The GLSC should do a consultation with the community, get an accurate description of the lands, do a good job of mapping that, and then do a good job marking posts in the ground,” explains Ellis. “But each one of those steps contains errors.”

According to the land tenure assessments, mapping errors have resulted in the loss of approximately 20% of titled village land. From the zoomed-out view of a national map, the way a border bends can seem arbitrary. But at ground level, the effects are devastating.

With the Land Tenure Assessments Complete, What Comes Next?

This evidence-based advocacy map arms Guyana’s indigenous peoples in their fight for greater land recognition, says Graham Atkinson, project coordinator at the APA. And the battle will be waged on several fronts.

“The first step is lobbying the government,” Atkinson explains. That means presenting their findings to the nation’s president, Mohamed Irfaan Ali, in the hopes of securing a revision to the Amerindian Act of 2006, which lays out a cumbersome framework for indigenous communities seeking new land titles. Fortunately, Atkinson says that the office of the president has “signaled their intention to meet with us.”

Less than a year into the presidential term, Ali’s administration failed to allocate money in their national budget for revising the Amerindian Act: a vital step in achieving the sweeping reforms recommended by the report. Still, the APA is optimistic that progress is possible.

“We’re prepared to work with this government,” says George.

Should the Guyanese government fail to take up actions on their own, the land tenure assessments still hold value. Atkinson anticipates using them as documentation in court filings, with the hopes that successful litigation could create better protections. And they can be presented to international organizations, such as: the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (UNCESCR); and the state of Norway, which has given significant financial support to Guyana’s environmental preservation efforts.

For his part, McGarrell feels hopeful that the land tenure agreements will produce meaningful change, while still noting the fundamental injustice of a two-tiered system: where mining and logging companies get the right to destroy the earth in a matter of weeks, while indigenous people are slowed down by years of red tape.

“The government gets quite a bit of revenue from mineral extraction, and that’s pushed them to grant concessions willy-nilly,” he says. “We’ve been living here for generations, but it’s so damn difficult to get recognition. It’s not right.”

Guyana is one of the more heavily forested countries in South America, with over 87% forest cover, but gold and diamond mining have accelerated deforestation recently.

The nation is at the center of the Guiana Shield, a 270 million hectare eco-region which stretches across the northeast of South America, from Colombia to Brazil. Deforestation of the Guiana Shield could severely impact climate and biodiversity across the continent, with researchers predicting that losing just a quarter of the forests could result in temperatures rising up to 4°F locally, bringing drier weather to the Amazon basin, and causing hydro-climate disturbance as far as 2,500 miles away.

George says that, “Our call for rights and protections, our call for protection of our natural resources in Guyana, is not only for indigenous peoples. It is for all of us as Guyanese. We need to protect our waters. We need to protect our forests… we’ve protected that land since time immemorial. For generations. And that is what we’re seeking to do.”