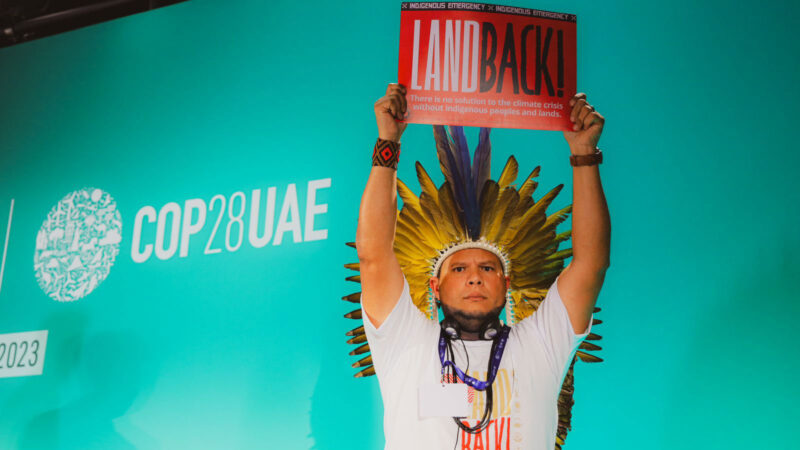

GATC members delegation at the Indigenous peoples’ press conference at the opening of COP28.

IMAGE CREDIT: Tukuma Pataxo | APIB

- The 2023 UN Climate Conference is expected to be the most significant since the Paris Agreement in 2015 as it will assess progress towards climate targets via the finalization of a ‘Global Stocktake.’

- Indigenous leaders from tropical forest regions will urge a reassessment of climate strategies that endanger nature and communities.

- Rainforest Foundation US participates in COP28, directly supporting Indigenous leaders from the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC), among other national and regional partners.

From November 30th through December 12, the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (known as COP28) will take place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Representatives from over 200 countries and organized civil society will debate crucial strategies for our future on the planet, including over 350 Indigenous people’s representatives.

In a dramatic and controversial shift from past conference presidencies, this COP will be chaired by an executive from an oil company, a major contributor to the climate crisis. It is also the first COP to occur after the world exceeded [1], albeit for just one day, the original 2°C global warming warning identified in the Paris Agreement.

Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) will participate in COP28, supporting Indigenous leaders from the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC), an organization that unites Indigenous peoples and local community (IP and LC) organizations from 24 countries in the Amazon Basin, Mesoamérica, the Congo Basin, and Indonesia, among other national and regional partners.

The GATC will demand urgent action to ensure countries are allowing IPs and LCs to influence the design and implementation of climate solutions that, in some regions, are already violating their land rights and causing harm to biodiverse ecosystems that store and absorb carbon.

Such projects can include the sale of carbon credits from Indigenous forests without community consultation; renewable energy initiatives like large hydropower dams that inundate traditional lands and destroy their forest-dependent knowledge systems and lifeways; and an increase in mining activities for metals and minerals essential for the renewable energy transition that harm local food and plant resources. In this case, mining activities lead to deforestation and pollution of water and soil on Indigenous peoples’ territories.

With calls for a ‘just transition’ ramping up on all continents, Indigenous leaders will argue that governments must heed the recommendations of UN climate [2] and biodiversity [3] experts. Only 14% of countries consulted with Indigenous peoples [4] in developing their most recent nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to climate goals. The same is true for plans to protect nature. In a review of 27 national preliminary plans to safeguard biodiversity, none include safeguards [5] for Indigenous peoples and local communities.

Meanwhile, as the launch of the Article 6 mechanism looms—effectively establishing the first global market for carbon credit trading, including forest carbon—Indigenous peoples are concerned about it meeting minimum standards to safeguard rights.

“How could a mechanism built by and for governments be held accountable? Indigenous leaders will be challenging that premise as it relates to its governance model as well as the design of its grievance redress procedures. The dense forests on Indigenous peoples’ lands are sure to be immediate targets for commodification upon the launch of the new market, which would put Indigenous peoples’ rights at high risk without the means to ensure protection.” – Joshua Lichtenstein, RFUS Program Manager

At COP28, they will ask world leaders not to repeat past mistakes by ensuring that safeguards and funding for Indigenous peoples and local communities are central to energy transition plans and renewed NDCs.

Here are the events that members of the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GATC) will join during COP28.

Why is COP28 so important?

COP28 represents a moment of global reckoning on progress made towards the climate agreement. According to the 2015 Paris Agreement, this is the year for the Global Stocktake, when nations come together to assess what actions have been or have not been taken. It’s also meant to be a time for nations to collectively decide on ways to close the gaps in ambition for emission reductions, adaptation (with a resource deficit estimated at up to $366 billion per year), and implementation. But the results are not encouraging.

Under the landmark Paris Agreement, countries committed to holding global temperature rises to “well below” 2° C above pre-industrial levels, while “pursuing efforts” to limit heating to 1.5°C. Those goals are an agreement. So far, country actions are leading us toward a catastrophic 3°C increase. Drastic cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, such as through the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels, are necessary within this decade to reverse this trend.

The Global Stocktake suggests that scaling up the land rights and heeding the values [6] and knowledge of Indigenous and local communities is not only based on scientific evidence [7] but also represents one of the world’s most cost-effective solutions for protecting forests and preventing damage that fuels climate change and biodiversity loss.

COP28 faces significant challenges, the first being conflicts of interest posed by being held in one of the world’s largest oil-producing regions. Leaked documents have revealed possible plans by the United Arab Emirates to negotiate fossil fuel deals before and during the conference.

The second challenge involves the effective operationalization of the newly established Loss and Damage Fund [8], which has already secured over $400 million at the launch of COP28 to assist countries ravaged by climate disasters. This pivotal initiative, underscored by global financial commitments, is designed to significantly support vulnerable communities. However, it faces critical challenges, including accurately defining ‘vulnerability’, ensuring fair contributions from donors, and managing the fund to efficiently address the projected annual loss and damage costs of $400 billion by 2030 in developing nations. Integral to its success is the expectation that the fund’s operations will uphold and promote human rights, ensuring the inclusivity of women, youth, and Indigenous peoples in its governance, which reflects key concerns raised during its establishment.

“Indigenous peoples and traditional communities are on the frontline of this climate crisis. Supporting them is a proven solution that has the potential to dramatically reshape global efforts to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. Achieving this means going beyond just recognizing the crucial role of Indigenous peoples in confronting the crisis, especially being among those most impacted by it, but scaling up effective community-based strategies, providing direct finance for those initiatives, and ensuring the rights of Indigenous communities to their lands and promoting their traditional forest stewardship practices.” – Maryka Paquette, RFUS Program Manager, who is in Dubai attending the conference

After the climate disasters of 2023, the hottest year on record, it is clear that implementing the Loss and Damage Fund is imperative to repair injustices and take immediate action. The most vulnerable—Indigenous peoples and local communities on the frontline of the climate crisis—cannot continue to bear the consequences of the crisis alone.

Science is clear about what needs to be done: Global greenhouse gas emissions must be reduced by 43% in the next seven years from 2019 levels. Doing so will mean more than a 66% chance of limiting Earth’s warming to 1.5°C with the least possible overshoot (temporary exceeding of temperature limits). Science is also clear about what we have not done. According to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), NDC targets currently set under the Paris Agreement would lead to an emission reduction of only 2% to 8% by the end of this decade. Carbon dumping into the atmosphere, which should have been decreasing by 7.6% per year since 2020, actually increased by 1.2% last year. If the current trajectory persists, the temperatures in this century will be double what the climate agreement prescribes.

“The Brazilian Amazon, where my people live, would become a desert if the global economic system continues to prioritize exploitation and profit over the health of our planet and people. If we don’t shift the current course of development now, it will be the end of our knowledge, practices, and traditions that animals, plants, and the climate depend on. If we do not take the necessary actions to conserve biodiversity, the world’s future and that of our people can be described in one word: desert.” – Cristiane Julião, from the Brazilian Amazon’s Indigenous Pankararu people, in an interview with The Guardian

Notes:

- Copernicus Climate Change Service: Global temperature exceeds 2°C above pre-industrial average on 17 November

- UNFCC: How Indigenous Peoples Enrich Climate Action

- IPBES: Indigenous and local knowledge in IPBES

- Ambio: Indigenous Peoples’ rights in national climate governance: An analysis of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs)

- Forest Declaration Assessment Special Report – Protecting Nature, Respecting Rights: Putting Indigenous and community rights at the heart of National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans

- IPBES: Decisions Based on Narrow Set of Market Values of Nature Underpin the Global Biodiversity Crisis

- Current Biology Journal: Indigenous lands in protected areas have high forest integrity across the tropics

- Climate Home News: Countries pledge $400m to set up loss and damage fund