- Indigenous peoples in Brazil’s Amazon are drawing on generations of ecological knowledge to adapt their agricultural practices in response to climate change.

- Communities are adapting by rethinking farming methods, planting crops in more strategic locations, preserving native seeds, and implementing sustainable practices to protect wildlife and their ecosystems.

- Indigenous elders are actively passing down traditional knowledge, ensuring the youth keep traditional agricultural practices alive and deepening climate resilience.

In the heart of the Brazilian Amazon, Indigenous communities are showing the world what true climate resilience looks like. The Amazon rainforest is one of the most vital ecosystems on Earth, but it’s also one of the hardest hit by climate change. Vast expanses of once-healthy forest have been devastated by record-breaking droughts, relentless fires, and unchecked deforestation. For Indigenous peoples, these changes go beyond environmental—they strike at the core of their cultural identities. Their forests are a source of food, medicine, income, security, and spirituality. Yet, in the face of a vanishing forest, Indigenous peoples in Brazil’s northern state of Roraima are drawing on generations of ecological knowledge to navigate the changes underway, ensuring their cultures, lands, and livelihoods endure. These communities are adapting in extraordinary ways, showing the world what true resilience looks like amid an ongoing environmental crisis.

Rainforest Foundation US (RFUS) has partnered with the Indigenous Council of Roraima (CIR) for over two decades to safeguard the rights of Indigenous peoples in northern Roraima. CIR’s work spans 35 Indigenous territories, home to 465 communities, including Macuxi, Wapichana, Ingarikó, Patamona, Sapará, Taurepang, Wai-Wai, Yanomami, Ye’kwana, and Pirititi. In 2024, with support from the Institute for Climate and Society, CIR published a report to document the adaptation efforts of communities across Raposa Serra do Sol—one of Brazil’s largest Indigenous territories, encompassing the Raposa, Serras, Surumu, and Baixo Cotingo regions. The report highlights how these communities are actively evolving their traditional agricultural practices to confront the challenges of a changing climate, offering vital insight into how Indigenous knowledge guides climate resilience.

Traditional Practices and the Rising Tide of Climate Change

Agriculture has long been a cornerstone of sustenance for Indigenous communities in Raposa Serra do Sol. Elders, once able to predict the climate by observing nature, are witnessing alarming changes as climate disruptions undermine traditional agricultural practices. The accelerated rhythms of nature are becoming harder to track, with out-of-season rains, increased flooding, stronger thunderstorms at unexpected times, rising temperatures, droughts, and wildfires.

“I have already lost many seeds during the harvest because of out-of-season rains,” said one community member from the Serras. “The weather has changed. It is hotter in April; it’s no longer like before when it was colder.”

Additionally, the growth of irrigated monoculture crops such as rice, has led to widespread deforestation, pesticide contamination of waterways, and excessive water consumption, compounding the challenges faced by communities. During periods of extreme drought, when water levels are dangerously low, these crops exacerbate the pressure on already limited resources.

The changes in weather are occurring mainly due to non-Indigenous people who brought a culture that is destroying our customs. We no longer have healthy food, the land is full of pesticides, and the waters are poisoned, killing the fish and harming other animals.

– Manoel da Silva Oliveira, Macuxi elder from the Maloquinha Community

Adapting to the New Climate Reality

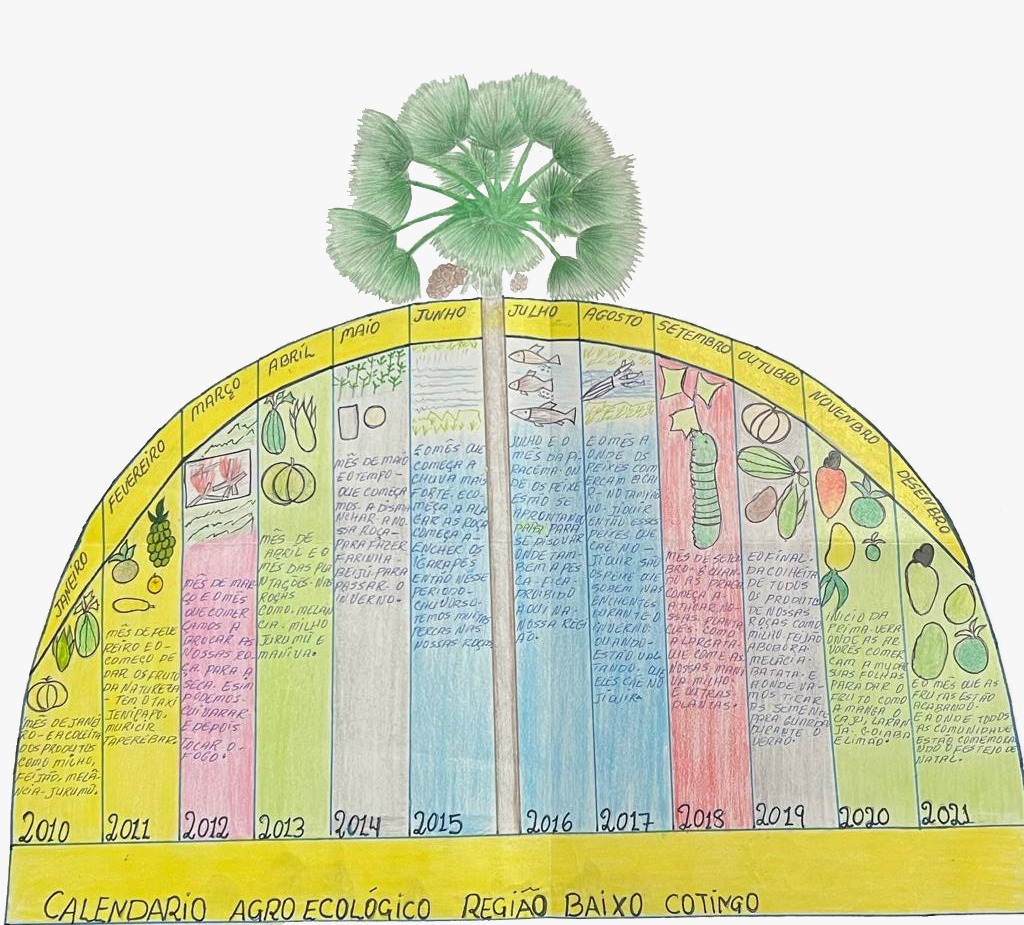

Despite the challenges, Indigenous communities in Raposa Serra do Sol are demonstrating remarkable resilience. Communities are incorporating the climatic changes they observe into ecological calendars to guide their agricultural practices. With support from CIR’s Indigenous Territorial and Environmental Agents, and through workshops and discussions with leaders, elders, teachers, women, and other community members, these ecological calendars reflect extensive research and the profound knowledge accumulated by Indigenous communities who have long observed the climate shifts affecting their lands.

The objective of the ecological calendar is to strengthen the Climate Change Adaptation Plan—the Indigenous Adaptation Plan. These calendars reflect how climate changes have impacted social and cultural life—from the people and crops to the water and forests that sustain Indigenous peoples.

– Sineia Wapichana, Environmental Manager of the Indigenous Council of Roraima (CIR), and Co-Chair of the United Nations Indigenous Peoples Caucus

Serras Region

- January: Intense summer with constant winds. Communities hold planning meetings before the first half of the month. This period marks the beginning of clearing and cutting primary forest (for family farms). Streams and lakes dry up, and people take the opportunity to fish using drag nets, seines, and bows.

- February: Strong summer continues with windy conditions, alongside clearing activities on the farms. Fruits ripen during this time, and fishing continues in the lakes and Quinô River.

- March: Burning of cleared farms begins, followed by the clearing of secondary forests. The cicadas start to sing.

- April: Jenipapo fruit begins to ripen, attracting various birds, including arancuã and sanhaçú, which feed on the fruits. Holy Week is celebrated, and communities engage in collective fishing using timbó, a root used to paralyze fish

- May: The rainy season begins, and tanajura and manivara ants take flight. This period also sees the emergence of mutambeira caterpillars on tree trunks or feeding on leaves, and it is the time for various plantings.

- June: Rainy weather and cloudy skies. Wild fruits like jaríi, bacurí, and cabeça de macaco (monkey head fruit) ripen, along with mangoes, while farmers clear their fields.

- July: Time to harvest ripe burití fruit, corn, and watermelon.

- August: Snakes begin to appear, accompanied by thunderstorms and grass flowering. Corn, watermelon, and other products are harvested and displayed.

- September: The end of the winter season. Mandi fish ascends the waterfall in the Quinô River. Corn and beans are harvested.

- October: Time for harvesting yuca and roasting flour. Yellow butterflies begin migrating east.

- November: Summer sets in, a time for community evaluations and central gatherings.

- December: The hunting season for Christmas and New Year’s Eve. Cashews ripen during this period.

Baixo Cotingo Region

- January: Summer, the time for clearing primary forest. It is also the season for araçá, mirixí (a local fruit), yellow mirixí, dove chicks, pada-pada, and galega (a type of fruit or bird).

- February: Summer, a time for harvesting burití fruit. Tortoises lay their eggs, and peccaries and monkeys give birth during this period.

- March: Mid-summer, marked by farm clearing and controlled burns.

- April: Winter arrives, bringing the time for planting corn, yuca, beans, acerola, and taxi (a local fruit).

- May: Winter continues with the harvest of taxi, mango, and jenipapo fruits. It’s also the reproduction season for tortoises and tapirs.

- June: Winter, a time for harvesting jenipapo and marfim (ivory tree fruit), when the fish begin their migration (piracema, the fish migration period).

- July: Winter, time for planting corn, hunting juriti birds, and sowing rice.

- August: Winter continues with the ripening of wild guava and burití fruit.

- September: Mid-summer, the season for harvesting sugarcane and ant nests, and hunting giant anteaters.

- October: Mid-summer, time for mango harvest.

- November: Summer, marked by the ripening of mirixí fruit and galega.

- December: Summer, a time for harvesting cashew fruit.

Communities draw on their ancestral ecological knowledge and these calendars to guide their adaptation efforts. In the Raposa region, for example, yuca—a staple crop—has become increasingly difficult to cultivate due to extreme summer heat. Irrigation is often impossible, causing the roots to dry out and rot. However, the communities’ deep-rooted knowledge of the crops allows them to select the most resilient varieties of yuca, such as the São Gabriel variety, which can better withstand extreme heat. Communities have created systems of exchange and donation of yuca roots, ensuring that all communities have access to the most resilient varieties.

Adaptation also means rethinking farming practices. As the climate grows more unpredictable, communities are planting crops in more strategic locations, avoiding areas prone to droughts. For example, beans, which are traditionally planted in summer, have become nearly impossible to grow due to the increasingly hot temperatures. The plants dry out and die before bearing fruit, leading to the loss of seeds that are important for the next planting. To combat this, beans are now planted in winter to ensure better production.

One solution we’ve implemented, particularly to support agriculture, is using solar-powered irrigation systems to extract water from underground sources. This allows for crops to grow even during drought. We’re actively working to find solutions to the climate crisis.

– Sineia Wapichana

Shifting weather patterns—often leading to weaker rainy seasons and harsher summers—make it difficult to predict planting and harvesting times, resulting in the loss of valuable seeds. To preserve seeds for future planting, communities employ traditional techniques—harvesting fruits, extracting the seeds, exposing them to the sun to dry, and storing them with ashes in suitable places to prevent weevil infestations.

Changes in climate are also affecting local wildlife. In Raposa, species once common in the mountains and along riverbanks, such as the araçá, a species of monkey native to northwest Brazil, are disappearing. Birds like the Jandaia Parakeet and Toucan, once abundant, have either migrated or vanished due to the destruction of their habitats by wildfires. Fishing, an essential part of community life, has also become more difficult as fish populations dwindle.

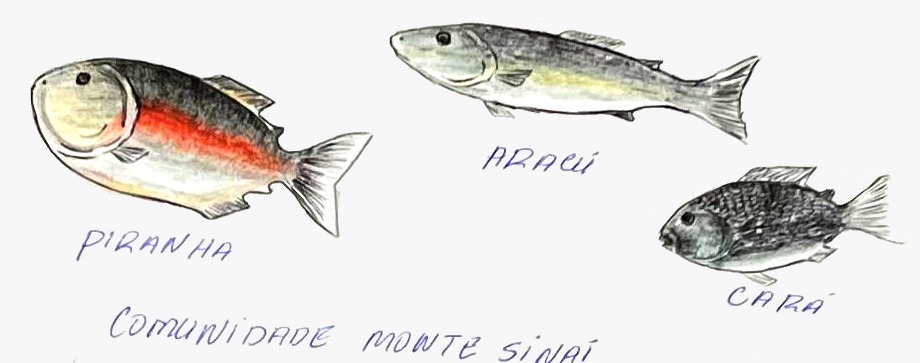

In the Baixo Cotingo region, fish are removed from rivers by commercial fishers using nets, particularly during the fish migration period, disrupting their reproductive cycle. In contrast, communities utilize sustainable fishing practices, using hooks and limiting their catch to ensure the survival of local species. And the loss of game animals, driven by poaching and encroachment from surrounding industries, has led Indigenous communities to cease traditional hunting of vulnerable species, such as the tatu-bola and tatu-peba armadillos, to protect their reproductive cycles and preserve these important species.

Indigenous communities have also launched fire brigades to control wildfires and combat deforestation, recognizing these efforts as vital to preserving animal habitats. These habitats provide shelter, food, water, and clean air—essential for wildlife to thrive. As climate change accelerates, these protective measures are becoming integral to daily life, ensuring the survival of these ecosystems.

In response to cultural shifts, there is a growing effort to ensure traditional knowledge is passed down to younger generations. In the Serras Region, Seed Fairs highlight family farming practices and facilitate the exchange of knowledge on traditional agricultural methods. Native seeds, known for their resilience and durability, are emphasized, reinforcing the importance of protecting them for the future. Youth in these communities are being actively taught about the significance of preserving seeds, respecting the land, and ensuring that traditional knowledge endures.

“The knowledge of the elders is very important for maintaining traditions and respect for nature. We understand that the knowledge of Indigenous culture is the best way to preserve the environment,” said a community member from the Surumu region.

Honoring Indigenous Resilience on Biodiversity Day

The ecological calendars carry a wealth of traditional knowledge, supporting the collective management of community farming, biodiversity, forests, and water. However, the climate imbalance is creating impacts that are often irreversible. We need urgent support to strengthen traditional Indigenous knowledge. These are the strategies we must pursue to preserve both this knowledge and our resilience, because Indigenous peoples are incredibly resilient.

– Sineia Wapichana

On this Biodiversity Day, we honor the Indigenous communities like those in Raposa Serra do Sol, whose wisdom is crucial for adapting to the impacts of climate change. Through their ancestral agricultural practices, they are nurturing the land while safeguarding the most biodiverse place on Earth—the Amazon. Indigenous peoples are not only the most impactful stewards of the forest, they are its strongest defenders, and their climate resilience holds the key to protecting the Amazon for generations to come. As the climate crisis continues to escalate, their resilience is a powerful reminder that it’s possible to adapt even in the most challenging circumstances.

Learn more about Indigenous-led rainforest protection, and keep up with the latest developments in our work by signing up for our email list today.