Month: April 2020

Voices from the Ground: COVID-19 Response in Loreto, Peru

Betty Rubio Padilla presenting information about the risks of COVID-19 to the Puerto Arica Community in the Napo River basin.

Voices from the Ground: COVID-19 Response in Loreto, Peru

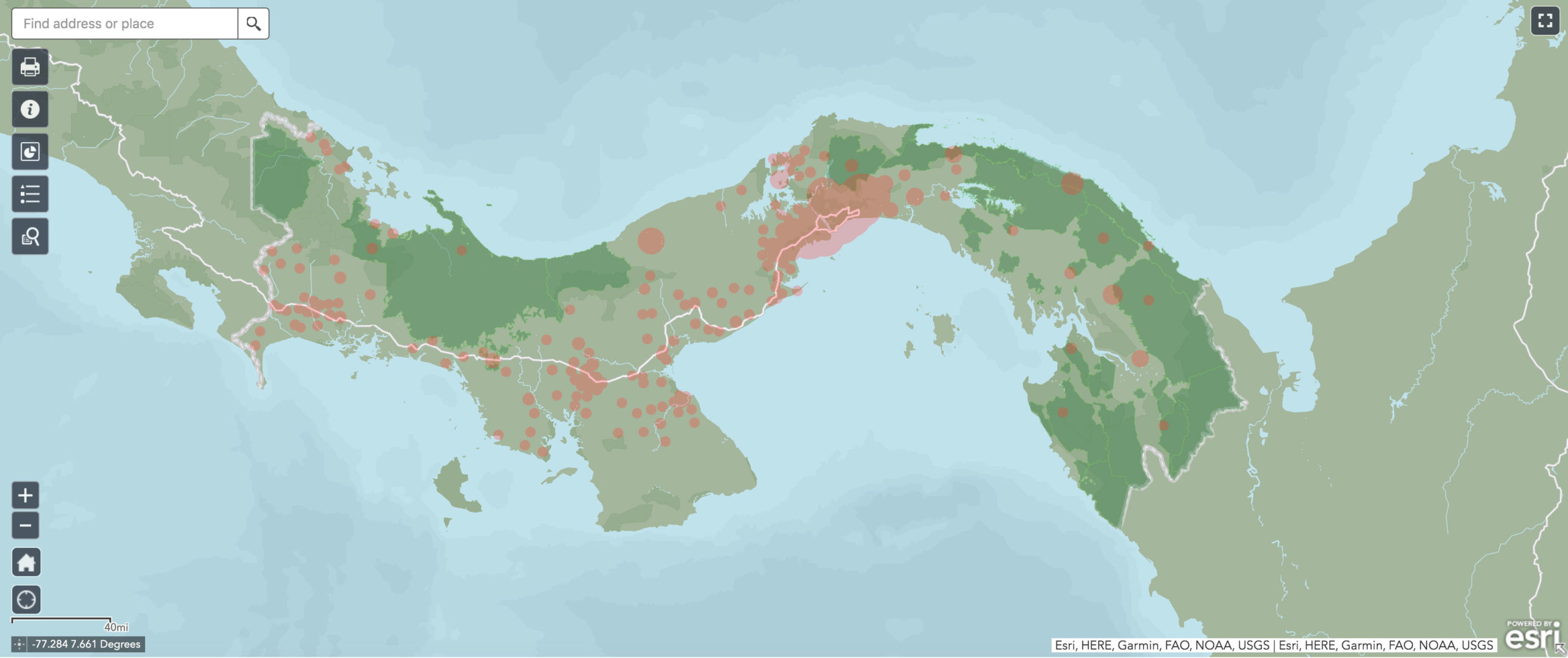

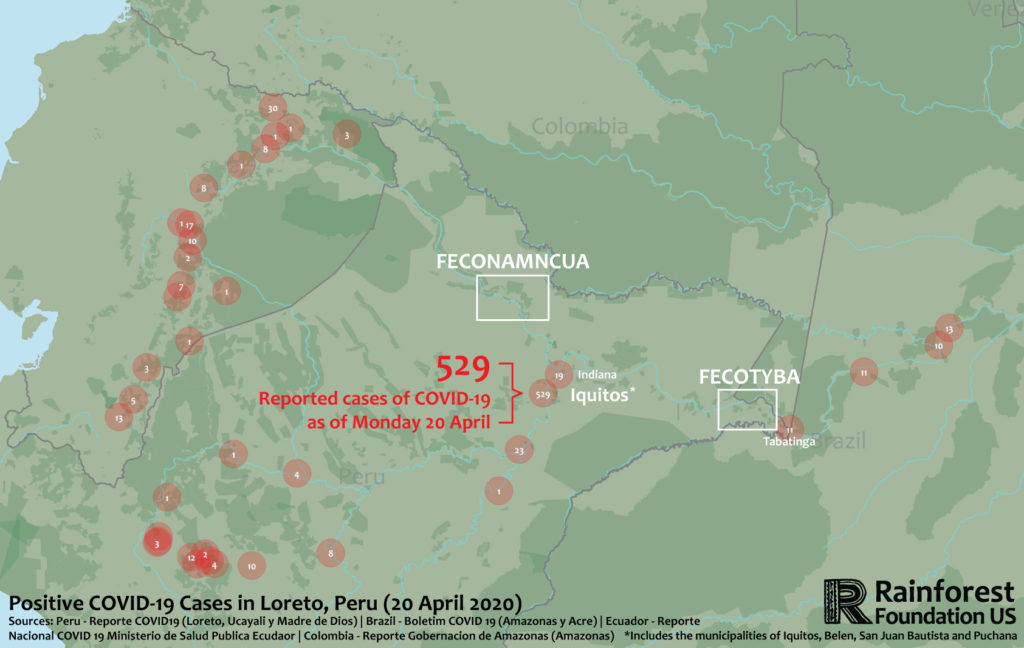

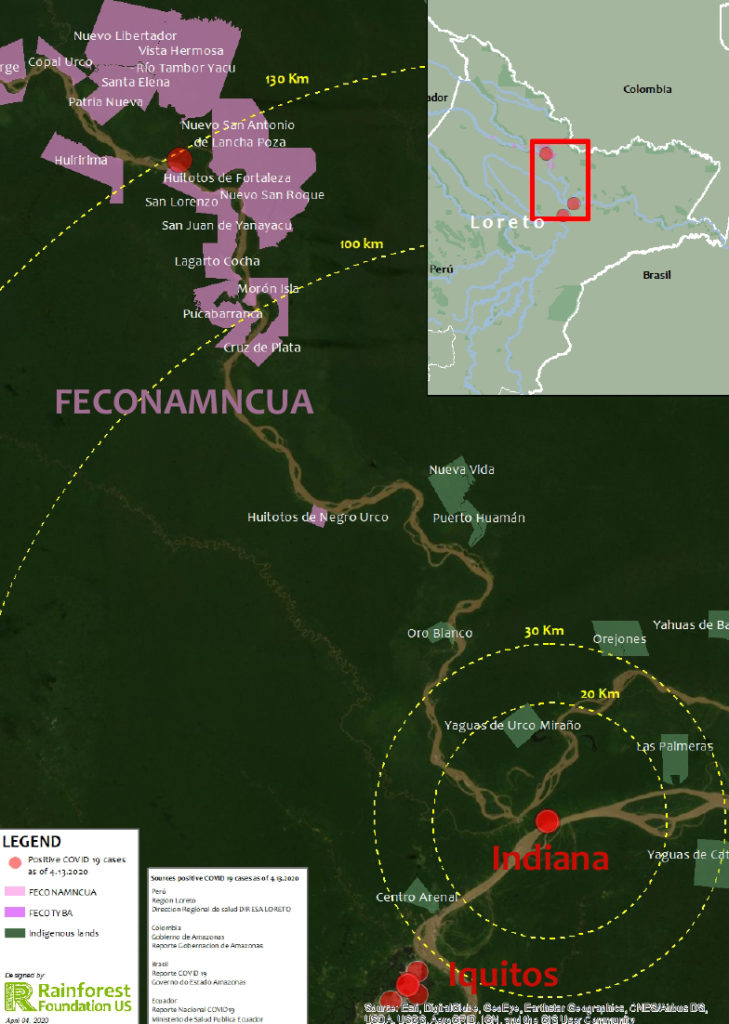

Indigenous Kichwa leader Betty Rubio Padilla, President of the Native Community Federation of the Medio Napo, Curaray y Arabela (Federación de Comunidades Nativas del Medio Napo, Curaray y Arabela, or FECONAMNCUA) and Ticuna leader Francisco Hernandez Cayetano, President of the Federation of the Ticuna and Yaguas Communities of the Lower Amazon (Federación de Comunidades Ticunas y Yaguas del Bajo Amazonas, or FECOTYBA), both affiliates of the Indigenous Peoples’ Organization of the Eastern Amazon (Organización Regional de los Pueblos Indígenas del Oriente, or ORPIO), are actively coordinating their response with Rainforest Foundation US and ORPIO, local government officials from the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Culture and Peruvian security forces to support local communities who are imminently threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic (see map).

Meanwhile, the Peruvian government has been strictly enforcing travel restrictions in Loreto, where they are based, to reinforce the national quarantine, which are negatively affecting indigenous communities’ access to basic necessities, medicine and communication. Rainforest Foundation US has been in regular communication with Betty Rubio Padilla and Francisco Hernandez Cayetano. Their testimony is shared below.

Rainforest Foundation US: How are you seeing COVID-19 impacting your communities?

Betty Rubio: The coronavirus is restricting travel for our community members to protect them from those who could be carrying the virus, especially if it is known that they are coming from the cities. People are really scared to leave their villages and we still do not have protective equipment, so we have to be very strict to minimize our contact with outsiders. However, because of these restrictions, many people are unable to talk or see their relatives in other communities. But what is making us start to worry is the fact that the travel restrictions are causing many, many communities to run out of food.

Francisco Hernandez: Our communities are tremendously concerned about the impacts of the coronavirus could have on them. We have never experienced an epidemic like this. Community members are frightened every time someone has to travel to cities for emergencies. Our communities are very close together and we cannot carry out social distancing like in the cities. In addition, we are very worried that our neighbors from the Brazilian cities of Tabatinga and Benjamin Constant are already infected and what that might mean for our exposure to the virus (See map).

The restricted travel due to the coronavirus keeps us from being able to travel to cities to sell our products and, visa versa, supplying the communities with needed provisions. Now the markets are empty and no outside food is coming to the community. People are starting to run out of food. There is nothing to buy and people cannot sell or trade. This is causing panic. Some communities do not have their own food supply.

Rainforest Foundation US: What measures are you taking to inform and protect the communities you represent?

Betty Rubio: As representatives of the Federation, we are taking great precaution as we communicate with community leaders about the risks of the coronavirus. Most communities do not receive information from the government or media. So we have had to do outreach ourselves to share how this disease spreads, how to protect ourselves, and how to respect the quarantine. We have told the community leaders not to interact with any outsiders, not even a family member who comes from the city. Also, we advised them to avoid going to any city even in the same district because there are many people who are gathering despite the State of Emergency decree. The infographic that ORPIO and Rainforest Foundation US produced has been very helpful because it is information that community leaders trust because it is from us. Because we all have it in our smartphones, we can show it over and over again. We try to reassure them that if they stay in the community where no one can infect them, they are going to be fine. But people are afraid.

Francisco Hernandez: With the Federation’s support, we are translating and distributing the ORPIO/Rainforest Foundation US infographics in the Ticuna language. Many Ticuna people do not speak Spanish well or read Spanish, so having the information in Ticuna has been very important. Now everybody knows about the coronavirus and are afraid. Now, they prohibit anyone from entering and we tell them to not go to Brazil right now, where there are already many cases of coronavirus. Because of our efforts, community members are not leaving their territories.

Rainforest Foundation US: Are you still experiencing threats to your territories, such as illegal logging and mining? If so, what measures are you taking?

Betty Rubio: The threats to the area in terms of illegal logging and mining have not stopped. These people continue with their activities knowing very well that the authorities are not going to be able to find them since they are in very remote areas. We are very concerned about this continuing. We are looking at how to inform government authorities about these illegal activities to bring the perpetrators to justice. But this will be difficult without the evidence that we usually acquire in our regular monitoring patrols. We cannot travel, but we want to inform the authorities that illegal activities are taking place and solicit their action.

Francisco Hernandez: We have threats in our communities caused by illegal loggers and drug traffickers who are taking advantage of the chaotic situation and lack of law enforcement. Previously, we have coordinated with local authorities, with our satellite-based community monitoring system. Despite the travel restrictions and enforcement of the quarantine, activities such as illegal logging, mining and land invasions continue. We are afraid to confront these actors because of health concerns. The authorities are busy with the enforcement of the quarantine. This situation is likely to result in increasing threats.

Rainforest Foundation US: What are your community’s needs at this time to confront the pandemic?

Betty Rubio: The most urgent needs right now in the Napo area are medicines. Since community members cannot leave their communities, they are isolated, without access to basic medical supplies. Because of this, they also do not have basic necessities, like soap or matches or salt. The local stores are in short supply because no one can transport the products. In addition, fuel is the fundamental need for the communities that do not even have access to electricity. But the ban on travel is affecting people’s ability to acquire fuel too.

Francisco Hernandez: Our communities urgently need food and basic medicine for common health problems. They need food because the markets are empty. They need medicines because the health posts are empty. There are no supplies. Another need is fuel. Why? Because if somebody comes down with the coronavirus, we will need to get them to a hospital. We do not have protective gear like masks and gloves that they say that we are supposed to wear. But there is nowhere to buy them here. We also need phone credit so that we can stay in contact with the latest information and in case of emergencies.

Read More

Voices from the Ground: COVID-19 Response in Roraima, Brazil

An interview with the Legal Advisor for the Indigenous Council of Roraima about adressing COVID-19 in his territory.

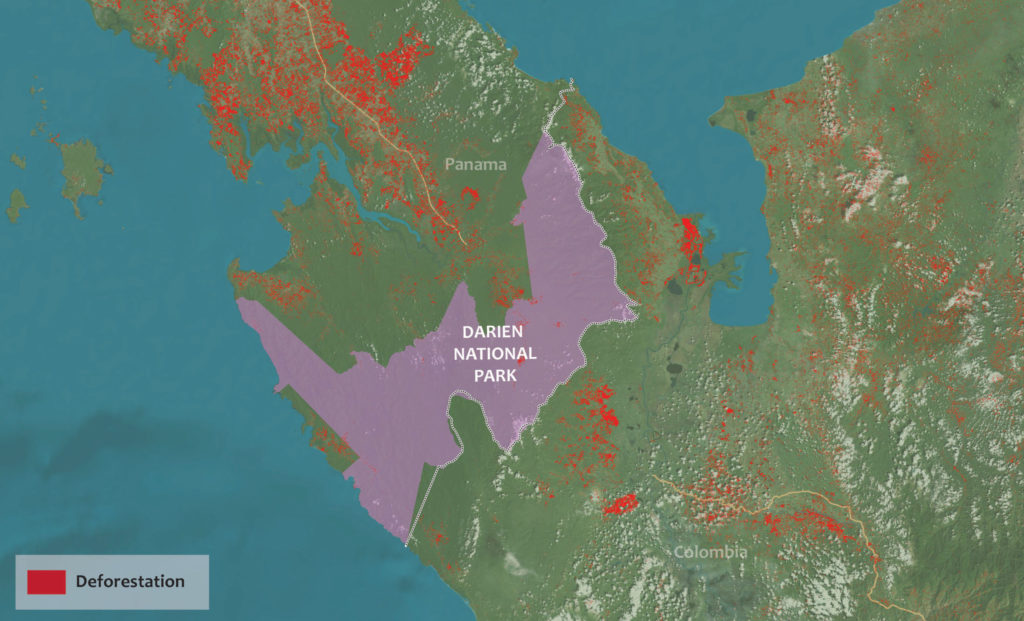

Voices from the Ground: COVID Response in the Darien, Panama

COVID-19 is straining the Embera and Wounaan peoples of the Darien as the threat of deforestation in their territories creeps higher.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Calls on Brazil to Protect the Yanomami

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has called on Brazil to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the Yanomami Territory.

Support Our Work

Rainforest Foundation US is tackling the major challenges of our day: deforestation, the climate crisis, and human rights violations. Your donation moves us one step closer to creating a more sustainable and just future.

COVID-19: Pueblos Indígenas de Perú Enfrentan Escasez de Alimentos y Deficiencias en Atención de Salud

COVID-19: Pueblos Indígenas de Perú Enfrentan Escasez de Alimentos y Deficiencias en Atención de Salud

El cierre total de sus territorios fue la primera medida que adoptaron las comunidades indígenas cuando el gobierno peruano, el 16 de marzo, decretó el Estado de Emergencia ante el avance del coronavirus.

Cerraron caminos, puentes, impidieron el ingreso de embarcaciones por ríos e incluso prohibieron los vuelos a lugares lejanos. Así, casi un millón de personas que viven en comunidades indígenas amazónicas de Perú apostaron por el aislamiento como la mejor forma de protegerse de la amenaza del nuevo virus.

Read More

Miners Out, COVID-19 Out: The Yanomami and Ye’Kwana People of the Brazilian Amazon Launch a Global Campaign to Expel Miners From Their Territory

Indigenous leaders demand the urgent removal of 20,000 illegal gold miners from their lands to prevent the spread of COVID-19

SOS Rainforest Live: Major Artists Unite in Support of Indigenous Guardians of the Rainforests Threatened by the COVID-19 Pandemic

On June 21st, major international artists will join in solidarity with indigenous peoples for a livestream concert to raise awareness and support for indigenous forest guardians under extreme threat from the coronavirus.

Voices from the Ground: COVID-19 Response in Roraima, Brazil

Junior Nicacio Farias Wapichana (in the black shirt on the right), Legal Advisor for the Indigenous Council of Roraima (CIR), gathering food and materials to deliver to villages in self-isolation to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Photo thanks to Comunicação Social Local Serra da Lua, with support from Conselho Indígena de Roraima (CIR).

Voices from the Ground: COVID-19 Response in Roraima, Brazil

This week, Junior Nicacio Farias Wapichana, Legal Advisor for the Indigenous Council of Roraima (Conselho Indígena de Roraima – CIR), spoke with Rainforest Foundation US about how indigenous peoples across the northern state of Roraima, Brazil, are taking measures to prevent the impact of COVID-19 on their communities.

Rainforest Foundation US: What are you hearing about how COVID-19 is affecting the region where you live?

Junior Nicacio: As of the latest report from the government, 49 positive cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the state of Roraima and 1 death: a driver for the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health (Secretaria Especial de Saude Indigena – SESAI). We have also received word of the first indigenous person who tested positive to COVID-19: a young Yanomami currently in Boa Vista, who at first tested negative but after a second round of testing came back positive and is now being monitored (1).

Rainforest Foundation US: How is information on COVID reaching your communities?

Junior Nicacio: CIR held our General Assembly that ended March 14, 2020, where community members first got an understanding of the depth of the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, our leadership decided to halt all fieldwork and focus 100% on the pandemic response.

Among some of the actions we have been taking are producing short videos, writing stories and preparing infographics on preventative measures in language that can work for our communities. We post these on social media and on our website; several communities have internet in their villages so this information is being disseminated virtually. Since so many communities receive the majority of their news over the radio, we have made radio programming a priority. We also have indigenous health care agents stationed in the communities who are helping to spread the word in our languages.

Our priority here is to get accurate information out about prevention and raise awareness among local community members in ways that work for them.

Rainforest Foundation US: What is the feeling circulating among community members about this situation?

Junior Nicacio: We are worried and concerned about the quickly-evolving situation around COVID-19 and, like everyone, wondering how long this is going to last.

We work directly with 246 indigenous communities in the state, and indirectly with many more. All have closed access into their territories. Cooperation between leaders and community monitoring teams led them to take the decision to close communities to the outside and actively monitor their entryways. Most territories have closed indefinitely, only allowing access for the most urgent needs.

We are most worried about the villages that have towns nearby – some are only 10-15 kilometers away – because there is easier access to those communities.

All of the villages are now going into voluntary isolation because life in our communities is collective, making it possible for the virus to spread quickly if it were to get in.

Rainforest Foundation US: What risks are you seeing COVID-19 presents for your communities?

Junior Nicacio: Some of our communities lie on the border of Venezuela and Guyana. Brazil officially closed border to those countries. However, some of our communities need to travel through Venezuela in order to get basic goods to their communities, so find themselves in a very difficult situation due to the border closing. This is the same with some communities bordering Guyana. These communities have found themselves cut off from some of the basic supplies they depend on, due to the closed borders.

Wapichana communities on both sides of the Guyana and Brazil border – because many of us have relatives or close family members on the other side – made a mutual agreement to close the border between our territories to prevent garimpeiros (wildcat miners) from crossing from Brazil into Guyana through our lands.

Another issue arising around communities that have closed their borders is an increase in threats from farmers who run large-scale agricultural operations and usually pass through our territories to get to their fields.

This happened recently in Truaru village, which is on the way to a large-scale soy plantation. When entry was barred, the operators grew angry. They even brought in the military police to pressure the community to open their border. The leaders explained that their passage through their lands posed a serious risk to their peoples’ health, and stood firm. A similar incident occurred near the village of Moscou, where the military police were again called in to apply pressure. The communities have had to explain they are following recommendations of the Ministry of Health in order to stop the spread of the new coronavirus in our communities.

CIR is encouraging all community leaders to stand firm in protecting their territories at this time. The farmers can take other roads to get to where they need to go. But the threats keep coming in.

Rainforest Foundation US: How are you seeing that the new coronavirus may be impacting—for better or worse—the existing threats to your communities?

Junior Nicacio: One of the main issues we have in our territories is illegal mining, which has not stopped due to coronavirus. In fact, it has increased.

On April 1st in Raposa Serra do Sol, community monitoring teams removed mining equipment and boats that the miners use to conduct their activities. The community leaders informed government authorities, including the National Indian Foundation (Fundação Nacional do Índio – FUNAI, the agency of the Brazilian federal government responsible for indigenous affairs) and the army, of what they were doing and that they were setting up a surveillance post on the Cotingo River that runs through their territory.

They will intensify their monitoring of the area and remove miners on their own, if they have to. They are worried that not only not only is mining illegal, creating a number of environmental problems that already affect the health of the river and nearby communities, but the miners can carry the virus, putting communities at even greater risk.

Rainforest Foundation US: How are you experiencing your government’s response to COVID-19, particularly as it relates to indigenous peoples’ reality in Roraima?

Junior Nicacio: The leaders of our communities informed government officials of our concerns around mining at our assembly in early March. But we have not seen them take action. That is why the community leaders along the Cotingo River took the initiative to confront the miners themselves, informing FUNAI of their actions every step of the way. They expressed their concern for this approach because the miners are armed and dangerous, but it was the community’s decision. They needed to take action to protect themselves.

To date, the state government of Roraima has not issued an emergency response plan to COVID-19 that responds specifically to indigenous peoples’ situation and concerns. There are 70,000 indigenous peoples in our state, with no government-backed plan to protect them.

There is a differentiated approach within the federal health system specific to indigenous peoples. We have health posts staffed with trained health professionals – doctors, nurses, etc. – who work with indigenous health agents to provide appropriate health care to our communities. Usually, those professionals rotate every 15 days, but CIR has recommended against that at this time. So, they are staying in place, working with indigenous health care agents to continue to provide services and information on the virus to the communities.

Beyond all that was mentioned before, CIR continues putting pressure and advocating for the communities’ needs. We continue to see similar issues in different communities without a response that is specific to indigenous peoples. We do not know how the government’s benefit program is going to reach our communities. CIR is advocating for a more urgent and human response—not only for indigenous peoples but non-indigenous peoples as well.

Rainforest Foundation US: What are your community’s needs and priorities at this time to confront the pandemic?

Junior Nicacio: Our isolation is a collective isolation. We have our own way of preventing a pandemic in our communities and it starts with taking all of the measures recommended within the community, while also preventing people from coming and going between the towns and villages.

Our question is: How long can we resist?

Our communities have fish, they have meat, and some local crops. But they need complementary food. They need medical supplies and services, especially for the elders. We cannot be taking them to hospitals for treatment at this point, so we need to be able to treat them at home.

Meanwhile, there is a shortfall of personal protective equipment and hand sanitizer in Boa Vista. We are told there is more arriving next week but we are already worried that this will be too late. There are over 200 of our leaders working on the front lines at road barriers, stopping cars, putting themselves at risk. Personal protective equipment and disinfection supplies are urgently needed. For now, CIR has started using homemade masks. But we still need medical grade personal protective equipment, especially to protect communities and leaders, in the event that positive COVID-19 cases reach our communities.

We have a fundraiser in place to help us secure the resources required to outfit our communities to protect themselves and to respond to emergency needs as they arise.

Rainforest Foundation US: What is giving you hope and strength to confront the challenges of this time?

Junior Nicacio: What gives me hope and strength is our unity. The whole CIR team is united in our concern for the risks that COVID-19 presents to our communities and are working on the front lines to support them in their preparations. I am encouraged by the leaders working day and night at the road barriers.

My hope lies in our unity against the pandemic, working to prevent spread in our communities. We are ready to fight. We are following all recommendations so we do not have to pay too high a price. The result we want is to have no communities affected. We are here to protect life.

Notes

(1) This interview was conducted on Wednesday 8 April and on the following day it was released that the young Yanomami Junior mentioned had passed away due to complications arising from his COVID-19 infection. More on this case can be found here.

Read More

Voices from the Ground: COVID-19 Response in Loreto, Peru

An interview with two indigenous leaders about their communities’ reactions to COVID-19.

Voices from the Ground: COVID Response in the Darien, Panama

COVID-19 is straining the Embera and Wounaan peoples of the Darien as the threat of deforestation in their territories creeps higher.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Calls on Brazil to Protect the Yanomami

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has called on Brazil to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the Yanomami Territory.

Support Our Work

Rainforest Foundation US is tackling the major challenges of our day: deforestation, the climate crisis, and human rights violations. Your donation moves us one step closer to creating a more sustainable and just future.

Stepping Into the Gap: Lessons from the Darien in the Face of COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples’ Response

A bulldozer rests in the middle of the village of Rio Hondo after cutting a road in from the Pan-American Highway.

Stepping Into the Gap: Lessons from the Darien in the Face of COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples’ Response

Initial reports from Rainforest Foundation US’s partners on the ground in Panama indicate that miners, loggers and traffickers are exploiting the global shutdown to increase activity, and expand into new territories. As the pandemic closes down businesses, including many routine government functions, and attention is drawn elsewhere, there is a real risk that unscrupulous actors will take advantage of the crisis to occupy new lands and expropriate the valuable natural resources that indigenous peoples in the region depend on.

A lesson from the Darien

Amidst the uncertainty and anxiety of COVID-19, this experience offers a reminder of how epidemics have shaped cultures and landscapes over time.

History shows that disease and epidemics have had a major impact on the indigenous peoples of the Americas and by proxy the rainforests they managed. By some accounts, measles and smallpox wiped out up to nine tenths of many indigenous populations—often reaching communities years ahead of the first Europeans to step foot on their lands—leveling immense civilizations, leaving the world with the mistaken impression of barren continents.

In the easternmost province of Panama bordering Colombia, the Darien is currently home to dozens of indigenous communities rich in culture and in the biodiversity that surrounds them. The landscape contains one of the largest intact forests in Mesoamerica and, in a twist of fate, remains standing in large part out of concern for the spread of Foot and Mouth Disease from South America to Central and North America.

Foot and Mouth Disease is a viral infection that attacks hooved animals such as cattle, pigs, and goats causing a high fever and blisters on the feet and in the mouths of animals. Outbreaks have been recorded worldwide since the mid 20th century, causing entire populations of livestock to be eradicated to control the spread of the disease. Given the rapid evolution of the virus, vaccines are regularly updated to be effective against new strains as they emerge.

The only interruption in the 18,640-mile-long Pan-American Highway that extends from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego on the southern tip of the continent is 106 kilometers of rugged mountains and dense tropical forests separating Panama from Colombia, known as the Darien Gap. Roadless by design, these lands are the ancestral home of the Emberá, Guna and Wounaan peoples who have defended them against outside encroachment for generations.

Plans to construct a road connecting North and South America have abounded for centuries. One of the more formidable initiatives was launched by the United States government in the 1970s. The U.S. earmarked $100 million to complete the missing stretch of the Pan-American Highway. However, environmental, human rights and especially epidemiological concerns ultimately cut the project short. Panama at the time had no occurrence of Foot and Mouth Disease. Although thousands of cattle were vaccinated and quarantined against the disease on the Colombia side of the border, the virus was not contained to the degree that would have permitted the highway project to continue as planned. The effort was ultimately abandoned in 1975.

The Darien remains a signature case in how epidemiological concerns affected, and ultimately protected, a landscape and its peoples. By 1980 the Panamanian Government formally protected much of the region within the Darien National Park. Soon after, the UN declared the area a World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve.

The Darien under COVID-19

While the Darien is no longer an active target for highway development, the indigenous peoples and forests of the region are facing a growing list of threats that could be exacerbated by the introduction of the novel coronavirus.

The lack of roads has largely spared the region from many of the threats facing other Central American forests, such as clearings for cattle ranching and intensive agriculture. The dense forest canopy, however, lends cover to an illicit economy of drug trafficking, human trafficking, land trafficking, and land invasions that flows through the Darien.

Under normal circumstances these activities threaten the lives and forest-dependent livelihoods of the indigenous Wounaan, Emberá and Guna communities in the region. Indigenous leaders are threatened or extorted by criminals passing through their territories, and whole swaths of their land become inaccessible for farming or hunting because the risk of encountering armed groups is too high. Despite protections, deforestation in the area over the past decade has been rampant, in large measure still driven by the expansion of cattle ranching, commercial and small-scale farming and the legal and illegal trade in timber.

The short-term risks of intrusions into isolated indigenous territories includes the spread of COVID-19 to communities who have few natural immunities and some of the lowest level of access to health services of all Panamanian citizens. The loss of elders, being particularly vulnerable to this strain of virus, could mean the loss of volumes of ecological and cultural knowledge that keeps these communities vibrant and thriving.

Over the long term, intrusions could spur increased deforestation and fragmentation of the forest which leads to a decrease in ecological function. Furthermore, the social fabric of the communities could be threatened as additional rounds of deadly conflict erupt between indigenous peoples defending their territories and invading loggers, ranchers and colonists.

Indigenous peoples prepare against COVID

Rainforest Foundation US’s partners in Panama, including Wounaan, Embera and Guna civil society organizations and the National Coordinating Body of Indigenous Peoples in Panama (COONAPIP), have been working with the government to translate COVID-19 prevention information into the seven indigenous languages spoken in the country and coordinate a safe way to deliver emergency supplies to communities that have been cut off from access to regional towns and cities. Some indigenous territories have cut roads or blocked rivers in an attempt to protect their communities from outsiders who could bring in the virus.

Rainforest Foundation US is looking for ways to mobilize further support to COONAPIP and others as new and urgent needs arise. Over the long term, strengthening territorial control based on clear and legally recognized land rights will ultimately be the best way to protect the cultural and biological diversity of the unyielding Darien Gap.

At this time COVID-19 may be the greatest risk to these lands, but if nature tells us one thing about the lessons learned from the Foot and Mouth Disease epidemic it is that respecting the “gaps” between us is sometimes the wisest way to keep people and landscapes healthy.

Read More

Miners Out, COVID-19 Out: The Yanomami and Ye’Kwana People of the Brazilian Amazon Launch a Global Campaign to Expel Miners From Their Territory

Indigenous leaders demand the urgent removal of 20,000 illegal gold miners from their lands to prevent the spread of COVID-19

Murder of Two Yanomami by Illegal Miners Heightens Fears of Renewed Cycle of Violence in the Brazilian Amazon

The murders reinforce the need for the Brazilian government to immediately expel the more than 20,000 miners illegally operating on Yanomami land.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Calls on Brazil to Protect the Yanomami

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has called on Brazil to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the Yanomami Territory.

Support Our Work

Rainforest Foundation US is tackling the major challenges of our day: deforestation, the climate crisis, and human rights violations. Your donation moves us one step closer to creating a more sustainable and just future.